1

Isola Sacra index

Speciale sectie over de Romeinse begraafplaats van Portus (Engels)....

The asphalted part of the Via Severiana outside the necropolis, leading to the entrance.

INDEX

Choose one of the items below!

2

Introduction

Mosaic in front of tomb 43.

"This is a place free of fear!"

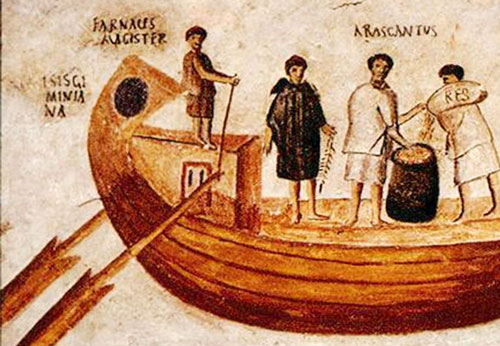

This Greek text was placed in front of the entrance of one of the tombs on the ancient Roman burial place. The text forms part of a mosaic on which we can see two sailing vessels entering the harbour of Portus. For the "inhabitants" of this necropolis, the text had a double meaning. The vessels were brought into a place outside the reach of the dangerous sea and, similarly, the deceased had, by taking his last boat trip over the river Styx1 , changed his worldly vale of tears into the eternal peace of the underworld. For me, as the author of this section of the website, there is a third sense.

Floor mosaic at the necropolis entrance. As so many others I'm very interested in people, their behaviour, thoughts and feelings. People not as a group, but as individuals. Each person feels himself standing in the centre of his own existence. For him or her everything is related to his own ego. Questions like 'who am I', 'where do I come from' and 'where am I going to' are quickly put. Questions which are not easy to answer and often give you a certain fear for the unknown. We have to realise, however, that in this we are not standing alone. Many have proceeded us and many will follow. 2 . I was immediately impressed by this spot. After reading some articles and especially the book of the British historican, Russel Meiggs, "Roman Ostia", I understood that I had to do with an ancient city that rose and fell into decay together with Rome. A city populated by ordinary people like you and me. A city where, walking through the now deserted streets, you might expect an ancient inhabitant coming out of a door or sitting on a public toilet.

The ‘Isola Sacra’ quarter in Fiumicino. Nowadays we can still find the name Isola Sacra (Sacred Island) on traffic signs in the neighbourhood of the airport of Rome. Here we have to do with a district of the present city Fiumicino, a coastal town on the west side of Rome. Only a few Italians can explain you why that particular part of Fiumicino has that name and even less people are able to give you any information about the origin of the name. We have to admit, for an island you have to look twice and any trace of sacredness is far away. Even the ancient Romans would be surprised when hearing this name.

The island between Ostia and Portus formed by the Tiber, the Fossa Traiana and the sea. As far as we know, even the ancient Romans didn't use the name Isola Sacra. In the fifth century AD an ancient writer, called Aethicus of Istria, mentioned in his "Cosmographia" the place as "Libanus Almae Veneris"3 . In 536 Procopius used the name Isola Sacra for the first time in his "De bello gothico" 4 . Why he called the piece of land 'Isola Sacra' is not quite clear. One of the reasons could be the presence of the basilica of St. Hippolytus, an early Christian martyr from Portus. This basilica was built at the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth century, perhaps on the remains of a Roman temple dedicated to Isis. In the sixties of the 20th century during excavations on this location there has been found a statue of this goddess.

The extended part of the Fossa Traiana in Fiumicino, called the Fiumara Piccola. At the beginning of the first century AD there was already a road between Ostia and Portus, the Via Flavia, later called the Via Severiana. On the south side you could reach Ostia probably via a ferry, and on the north side there was a bridge over the Fossa Traiana, the 'Pons Matidiae' to enter Portus. Not long after the construction of the new harbour, the people of Portus started to bury their dead along this road. According to the Roman law this had to be done outside the city. This part of the website will give you an impression of this unique necropolis. Of the original road, approximately 1300 feet has been preserved, including the part along the necropolis. Research has shown that the Via Severiana had a width of 35 feet and was divided into two separate lanes. The borders of the road were formed by a 3,65 feet thick wall. Each 10 feet there was a buttress to support the wall.

The Via Severiana at the necropolis looking towards Ostia. The rediscovery of the necropolis

Part of portrait of Emmanuel Théodose 5 The French cardinal was sent to Rome as an ambassador, became Dean of the Sacred College, and consequently Bishop of Ostia between 1700 and 1715. We know that he excavated a big tomb belonging to the family Caesennii. Several inscriptions have been found and published on his behalf. Unfortunately the originals are lost today and the location of this tomb is unknown. According to the publications it measured circa 88,8 x 28,4 m. A tomb of that size is nowadays unknown on the necropolis of Isola Sacra.6 . In this section of the website we will also describe these graves, as far as possible. Because these graves are located close to the Trajan's Canal, we refer to them as the Canal tombs to distinguish them from the large necropolis. The graves are located along the road that runs from Isola Sacra to the centre of Fiumicino. You're not allowed to enter this site but you can see the tombs from the road.

Excavations of the Isola Sacra necropolis in 1938 (Photo's Soprintendenza Ostia Antica). The cemetery we see today wasn't the only Roman cultivation on the artificial island. Excavations by Fausto Zevi in the sixties of the last century brought to light the remains of buildings on the Ostia as well as on the Portus side7 . These buildings served mainly harbour activities.

No tombs of rich people or men of standing have been found in the necropolis. The tombs we know today were meant for the local middle class, their servants, slaves and freedmen. With the exception of a single sarcophagus, we don't find traces of Judaism or Christianity. Also tombs of followers of other foreign religions are lacking. Almost all 'inhabitants' of this necropolis were Roman citizens and believers of the official Roman religion.

Sources Russel Meiggs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

1: De Styx was de mythologisch rivier waarover de overledene, na betaling van een muntstuk dat aan de dode werd meegegeven in zijn graf, door de veerman Charon naar de onderwereld (Hades) werd gevaren.

2: Read our article Alberino Vicari "Il Biondo" .3: The paradise of Venus4: Four books written by the Greek historican from Caesarea Maritima, Procopius, in which he described the Italian campaigns by Belisarius and others against the Ostrogoths.5: Le cardinal de Bouillon painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743), 1707, musée Hyacinthe-Rigaud, Perpignan.6: See our article 'Eventually, it's all about people' .7: For more information about other classical buildings at the Isola Sacra, see https://www.ostia-antica.org/isola/text-menu.htm

3

Ostia

"The river widens considerably as it reaches the sea and forms large bays, like the best sea harbours. And, most surprising of all, it is not cut off from its mouth by a barrier of sea sand, which is the fate even of many large rivers."

"Ships with oars, however large, and merchantmen with sails up to 3,000 (amphorae) capacity enter the mouth itself and row or are towed up to Rome; but larger ships ride at anchor outside the mouth and unload and reload with the help of river vessels." 1

At the end of the first century BC Dionysius of Halicarnassus described the mouth of the river Tiber. For Rome the river had been the most important overseas supply route for goods, especially grain. 2 , fourth king of Rome, decided that it was time to bring the road between Rome and Ostia under the jurisdiction of Rome. Round about 620 BC he reorganized the salt making and founded the first Roman colony in the angle between the mouth of the Tiber and the sea. He called that first dwelling after the Latin word for "mouth", Ostia.

Memorial table originally attached above the eastern citygate, the Porta Romana.

Mosaic with a Roman trading ship 3 , shops were opened and the local middle class increased explosively. At the height of its prosperity, in the second century AD, about 40,000 people were housed in Ostia. The city developed then as a real city with its own temples, bathhouses, a theatre, shops, warehouses, construction places, workshops, guilds and so on. 4 , a four-storied lighthouse was placed. Round about 110 AD the emperor Traianus enlarged the new harbour with a large landlocked inner hexagonal basin. The harbours were connected with the Tiber by channels.The remains of the northern pier of the harbour basin of Claudius. In the background, the buildings of Fiumicino Airport, Leonardo Davinci.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

1: Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Roman historian, rhetoric and writer. He was born in Turkey in 60 BC and died in Rome in 7 BC. Writer(in Greek) of 'Roman Antiquities'2: Ancus Martius ruled 24 years from 640 till 616 BC3: Read the article 'Overseas Trade' 4: In 37 AD Caligula transported an obelisk from Alexandria to Rome, via Ostia and the Tiber. It was to be erected on the spina of the Vatican Circus. The ship used for this was subsequently sunk between the piers of Portus, Claudius' new harbour, and used as the foundation for the lighthouse.

4

Tomb types

This part of the website will inform you about the kind of burials and about the architecture of the funeral buildings in the necropolis of Isola Sacra.

When Portus was built in the middle of the first century AD, the dead were always cremated in so called public ustrina1 . This custom continued till the reign of the emperor Hadrian (117 AD), when burial was introduced and for a long time cremation and inhumation went side by side.

Tomb of Priscilla at the Appia Antica in Rome2

Amphorae as final resting place in a grave on the east side of the cemetery. Simply burials on the 'Field of the poor' on the Isola Sacra.

Many of the simplest graves have been found in the area called "Field of the poor" or, as the Italians call it, 'Campo dei poveri'. The field is located behind tombs 38 - 43. During the excavations of 1988-89, 650 small graves were found. Most of these graves are covered again and can't be seen anymore. You will notice, however, another type of tomb in the Campo dei poveri, the so called 'tomba a cassone'. This tomb has the shape of, as the Italian name says, a big chest. Sometimes the owner tried to imitate the larger and more expensive monumental tombs by adding an aedicula3 , a tympanum4 or even a fake door. The "tomba a cassone" is not found just in the "Campo dei poveri". You can find them also in other parts of the necropolis.

Tomb 52 (foreground) and tomb 53. The "tomba a cassone" was well known along the entire coast of the Mediterranean. In Rome, however, this type of grave was hardly used. In Portus we find a concentration of these tombs. It probably tells something about the cosmopolitan character of the population of Portus.

The libation gap in the top of a "tomba a cassone" (tomb 62). 5 purposes. From left to right: tomb 1, 51 and 56. The majority of the tombs in this necropolis are 'tombe a cella'. This means a tomb with one or more burial chambers. They were detached or part of a row. 6 . Inside, they all had a fixed design, with the exception of tomb 75, built for three families, and tomb 34, probably belonging to a collegium funeraticium , a funeral association.

"Small bricks, regular and manufactured with care, selected on size and colour; An entrance consisting of two jambs with an architrave of travertine; Brick columns with capitals, made of several materials, on top; A marble slab with inscription, surrounded by a frame, above the entrance; Two small windows in one line with the inscription; A relief depicting the profession of the tomb owner; A tympanum in the top part. This was not always the case, but many of the tombs with burial chambers contained several of these elements".

There are still some examples of façades built in a combination of brick and tufa (opus reticulatum ), but often reticulate was only used for the back and side-walls. columbaria . The urns with the ashes of the dead were placed in semicircular or rectangular niches in the walls. Normally each niche contained two urns. These niches were built alongside a larger and better decorated central niche.

Because most of the tombs were used for a long time, after a while all the niches were filled. New space was often found by adding an enclosure to the front. The walls of these enclosures too were occupied by niches.

Biclinium in front of tomb 15 biclinia , were built on either side of the entrance. biclinia had to make way to new tombs. arcosolia7 . Later on, small niches were replaced by arcosolia and in new tombs the number of arcosolia increased. Tomb with arcosolia in the walls and formae in the floor. arcosolia are uneconomic in space, soon the area underneath the floor was also used. The floor was divided by brick walls into a series of graves, called formae , sometimes one row on top of another. arcosolia or formae without a sarcophagus. The arcosolium itself was closed by a rough wall, sometimes plastered, imitating marble, or by a marble slab. The latter are plain or decorated. Formae were often covered by the mosaic or marble floor of the burial chamber. arcosolia . Supports were built against the walls to carry sarcophagi. Marble was reused.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

Ida Baldassare, Irene Bragantini, Chiara Morselli and Franc Taglietti - Necropoli di Porto, Isola Sacra (Roma 1996).

1: An ustrinum (plural ustrina) was the site of a cremation funeral pyre whose ashes were removed for interment elsewhere (Wikipedia).2: Photo Notafly (Wikipedia)3: A small shrine4: A semi-circular or triangular decorative wall surface over an entrance, door or window.5: Libation was a religious act in the form of a liquid offering, most often unmixed wine and perfumed oil (Scheid 2007, p. 269).6: A Roman foot (pes, plural: pedes) measures 296 mm.7: Arcosolium (plural arcodolia): from Latin arcus, 'arch', and solium, 'throne' (literally 'place of state')

5

100 tombes

In this section we shall look at the 100 tombs on the west side of the Via Severiana. They are numbered from 1 to 100. Clicking on the word "map" on each page brings you back to the overall map of the necropolis and to the 100 buttons corresponding with the numbered tombs. Use the scroll bar below the map to see all of it. Placing the cursor on the tomb number on each page shows you the relevant part of the map.

{loadtombes}

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

Hilding Thylander - Inscriptions du port d'Ostie (Lund C W K Gleerup 1952).

Ida Baldassare, Irene Bragantini, Chiara Morselli and Franc Taglietti - Necropoli di Porto, Isola Sacra (Roma 1996).

6

Canal tombs

In 1938 a second part of the Isola Sacra necropolis was excavated. This section is located beneath a farmyard and is covered with soil again. 1 .

Plan with the tombs excavated since 1925 (Canal tombs), 1936 (covered) and 1930 (100 tombs). Coming from Fiunicino Sud you find the Canal tombs in the Via Redipuglia. Along this street. When I noticed the tombs for the first time, I saw a small, bad railed excavation with a number of tombs. A large sign, which was completely faded, stood desolated at an unreadable distance away from the fence.

Map of the Canal Tombs. Click on one of the following letters for the description of the tomb.A B C C3 D E F G H I L M N O

The street that divides the tombs into two blooks looking northward. The block of tombs is divided in two parts by a street running north-south.

Many sarcophagi, paintings and inscriptions have been found. They are all stored in the depots. When the necropolis wasn't used anymore, the tombs changed into a place for garbage. Many fragments of pottery did not belong to the inventory of the tombs, but were broken tableware and refuse from the nearby harbour.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

1: The name of this cluster, the 'Canal Tombs', has been given by myself, because of its location so near by the Canal of Traianus (the 'Fossa Traiana').

7

Canal tomb A

The street looking north. On the left side the remains of tomb A. On the right side the northern corner of tomb H. The entrance in the middle

Tomb A is located on the right side if we enter the street from the north. It forms one unit with tomb B. Both tombs are badly preserved. The entrance of tomb A, of which little remains, is turned towards the street. The threshold lies above street level and steps were probably used to enter the tomb. No traces of an inscription have been found. In the lower part of the walls of the burial chamber are three arcosolia. The upper parts were reserved for smaller niches containing urns.The heavenly damaged entrance of tomb A. Back to introduction Canal Tombs

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

8

Canal tomb B

The entrance from tomb B seen froom tomb I. On the left side the façade from tomb C.

Tomb B has a door towards the street. The travertine door jambs and architrave are still in place.

FECIT SIBI ET L(ucio) SCANTIO L(uci) FIL(io) EPARCHICO FILIO SVO ET SVLPICIAE M(arci) F(iliae) IVLITTAE NEPOTI SVAE ET LIBERTIS SVIS LIBERTABVSQVE POSTERISQVE EORVM H(oc) M(onumentum) H(eredem) E(xterum) N(on) S(equetur) IN FRONTE PED(es) XII IN AGRO PED(es) XIII

This tomb was built by Scantia Silvina, daughter of Caius. It was meant for herself and for Lucius Scantius Eparchicus, son of Lucius, her son, and for Sulpicia Iulitta, daughter of Marcus, her granddaughter, and for her freed slaves, and the descendants. The tomb could not be inherited by strangers. The measurements were twelve feet in front and thirteen at the back.

The owners of tomb B were related to the owners of tomb 55. Tomb 55 was built by a certain Scantia Salvina, the sister of Scantia Silvina, and the mother of Sulpicia Iulitta.

Back to introduction Canal Tombs

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

9

Canal tomb C

On the left hand the façade of tomb C. Notice the angle of the wall and the indentations Tomb C is a large tomb with its façade alongside the passage, but at a different angle than tomb A and B. The façade has been preserved till the upper cornice of the wall. Below that cornice was a series of letters, made of tuff, embedded in the bricks of the wall. The only one found in place was the letter D, probably part of the letters:

H(uic) M(onumento) D(olus) M(alus) A(besto)

Let this monument be free from intentional desecration(As far as we know this is the only case the expression has been used in this way.)

The entrance of tomb C is placed on the left side of the façade. During the Second World War the lower right side of the slab was damaged. The inscription is from the middle of the second century. It gives us the following information:

L(ucius) MINDIVS DIVS FECIT SIBI ET GENVCIAE TRYPHAENE CONIVGI INCOMPARABILI CVM QVA VIXIT ANNIS XXIIII MENS(ibus) III ET LVCCEIAE IANVARIAE MA RITAE ET ANNIAE LAVERIAE CONTVVERNA LI SVAE SANCTISSIMAE ET LIBERT(is) LIBERTAB(usque) SVIS POSTER(is)Q(ue) EOR(um) H(oc) M(onumentum) E(xterum) H(eredem) N(on) S(equetur) IN FRONTE P(edes) XXX IN AGRO P(edes) XXXXI

Lucius Mindius Dius has built this monument for himself and for Genucia Tryphaena, his incomparable wife, with whom he lived 24 years and 3 months; for Lucceia Ianuaria, his wife, and for Annia Laveria, his most chaste wife, and for his freedmen and freedwomen, and the descendants. The monument cannot be inherited by strangers.

Tomb C. Wall of the entrance on the right side. Tomb C: looking northward. Back to introduction Canal Tombs

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

10

Canal tomb C3

The entrance of tomb C3 and the right wall of the portico with the two arcosolia

The two arcosolia in the wall of the portico in front of Tomb C3. Between the portico and the entrance wall of tomb C3 stands a brick wall with two arcosolia. The upper one had a stucco front imitating the front of a marble sarcophagus with a hunting scene: a lion biting a deer and two horsemen fighting a lion and a panther. The cover of this 'sarcophagus' had a scene with cupids fighting wild animals.The 'sarcophagus', which had no inscription, has probably been brought over to the Ostian depots. The arcosolium below was painted, but was already during the excavations in a pitiable condition. The ceiling was painted with flowers, and the backside with two male figures, two birds and also flowers. This arcosolium was still closed; on the skeleton, covered with big tiles, no objects were found.

Considering the measurements mentioned in the inscription above the entrance of tomb C, we may regard tombs C and C3 as one unit, whereby C3 is the burial chamber and C the enclosure. The burial chamber (C3) was used for both inhumation and cremation. The back wall as well as both side walls have arcosolia on two levels and small niches for urns above. The entrance wall had only small niches for urns. Like the second arcosolium outside the entrance, the arcosolia on the second level inside the burial chamber were also equiped with imitation sarcophagi. Originally the second level consisted of one arcosolium flanked by two smaller niches. These were changed later into two arcosolia. During the same time of reuse a large podium was erected in front of the back wall, destroying a stucco panel. A small fragment, still visible during the excavation, showed that the panel was decorated with the same theme as the imitation sarcophagi.

The burial chamber called 'tomb C3'.

Mercury

Back to introduction Canal Tombs

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

11

Canal tomb D, E, F and G

D(is) M(anibus) TI(berius) CLAVDIVS TI(beri) FIL(ius) IVLIANVS FECIT SIBI ET CLAVDIAE DONATAE MATRI CARISSIMAE ET TI(berio) CLAVDIO DEME TRIO FRATRI CARISSIMO QVI VIXIT ANNIS XXI MEN SIBVS VIII DIEBVS XIIII ET CLAVDIAE IULIANE FILIAE DVLCISSIMAE ET LIBERTIS LIBERTABVS POSTERISQVE EORVM IN FR(onte) P(edes) XIII IN AGR(o) [---]

The inscription tells us that Tiberius Claudius Julianus, son of Tiberius, has built this monument for himself and for Claudia Donata, his dearest mother and for Tiberius Claudius Demetrius, his dearest brother, who lived twenty-one years, eight months and fourteen days, and for Claudia Juliana, his very sweet daughter, and for his freedmen and freedwomen, and the descendants. The area measures thirteen feet in width and in depth ... .

With the exception of the damaged north-eastern wall, the vault of tomb E was found almost intact, and on top several original roof tiles have been found.

Back to introduction Canal Tombs

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

12

Canal tomb H

and

Overview with tombs L, I and H successifuly on the right side.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

13

Canal tomb I

Tomb I leans for a large part against tomb H and has its façade towards the main street. The façade has been built up with inaccurate large brickwork and stretches of opus reticulatum.

P(ublius) AELIVS MAXIMVS FECIT SIBI ET VEIANIA IOTAPE ET LIBERTIS LIBERTA BVSQ(ue) POSTERISQ(ue) EORVM ITEM L(ucio) GENVCIO AEPAPHRODITO ET MARIAE DEVTERE ET POSTERISQ(ue) EORVM CVBICVLVM HYPOGEVM EIS DONATVM CONCESSOQ(ue) ITV AMBITV TRASITVM PER PORTICVM AEIS A P(ublio) AELIO MAXIMO

The inscription tells us that Publius Aelius Maximus has built this monument for himself and for Veiania Iotape, his freedmen and freedwomen, and the descendants; also for Lucius Genucius Epaphroditus and Maria Deutera and their descendant,s after a subterranean burial chamber has been given to them and the right to come and go and to walk under the portico has been permitted by Publius Aelius Maximus.

The door of tomb I gives access to tombs I, L, M, N, and O. When we enter tomb I, we find tomb L immediately on our right hand.

D(is) M(anibus) C(aius) CALPENIVS HERMES FECIT SIBI ET SVIS ET LIBERTIS LIBERTABVSQ(ue) POSTERISQ(ue) EORVM ET ANTISTIAE COETONIDI CONIVGI SVAE H(oc) M(onumentum) H(eredem) E(xterum) N(on) S(equetur) CVBICVLVM INTRANTIBVS AD DEXTRAM ET FORAS IN PAVIMENTO SARCOPHAGA ET CON TRA ET LAEVA PARIETIBVS DVOBUS AEDICV LAS CVM OLLIS ET SARCOPHAGIS FECIT

According to this inscription Caius Calpenius Hermes had built the monument for himself and his freedmen and freedwomen and the descendants and for his wife, Antistia Coetonis. The tomb could not be inherited by strangers. A resting place was made on the right side of the entrance and outside the tomb sarcophagi were placed under the floor, and in front of the entrance and on the left side in two walls aediculae have been made with urnes and sarcophagi. The inscription is from the time of Hadrian. Inside the tomb, on the right side, are two arcosolia with two niches above. In the right one was a shell of white stucco. A third small window was placed high in the back wall above a niche. To the left and right of the door three other niches, different in size, were grouped. Almost nothing of the painted stucco cornices which embellished the vault and the walls is left. The floor too was used as a burial place.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

14

Canal tomb L

When we enter tomb I, we find tomb L immediately on our right hand. The entrance of tomb L was provided with jambs, a threshold and an architrave made of travertine, and was flanked by two small windows, both with a terracotta plate. According to a marble plate with inscription above the door, tomb L belonged to Calpenius Hermes: D(is) M(anibus) C(aius) CALPENIVS HERMES FECIT SIBI ET SVIS ET LIBERTIS LIBERTABVSQ(ue) POSTERISQ(ue) EORVM ET ANTISTIAE COETONIDI CONIVGI SVAE H(oc) M(onumentum) H(eredem) E(xterum) N(on) S(equetur) CVBICVLVM INTRANTIBVS AD DEXTRAM ET FORAS IN PAVIMENTO SARCOPHAGA ET CON TRA ET LAEVA PARIETIBVS DVOBUS AEDICV LAS CVM OLLIS ET SARCOPHAGIS FECIT According to this inscription Caius Calpenius Hermes had built the monument for himself and his freedmen and freedwomen and the descendants and for his wife, Antistia Coetonis. The tomb could not be inherited by strangers. A resting place was made on the right side of the entrance and outside the tomb sarcophagi were placed under the floor, and in front of the entrance and on the left side in two walls aediculae have been made with urnes and sarcophagi. The inscription is from the time of Hadrian. Inside the tomb, on the right side, are two arcosolia with two niches above. In the right one was a shell of white stucco. A third small window was placed high in the back wall above a niche. To the left and right of the door three other niches, different in size, were grouped. Almost nothing of the painted stucco cornices which embellished the vault and the walls is left. The floor too was used as a burial place.

Sources Russel Meigs - Roman Ostia, At the Clarendon Press 1973

Guido Calza - Necropoli nell'Isola Sacra'(1940)

Dr. Jan Theo Bakker.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.