When you visit Ancona you will notice immediately that Ancona is a harbour city at the Adriatic Sea similar to Civitavecchia 2 at the Mediterranean Sea. The lovely ships in white or grey, bearing the marks of sea water and wind, cannot hide the involuntary harshness of the containers and the bustling confusion typical of areas busy with the traffic of men and goods waiting to board the ferry-boats. So far, not an attractive tourist city. But yet, like Civitavecchia, this landscape contains exceptional architectural landmarks. You will discover traces of an ancient past. Like the Roman triumphal arch, austerely resplendent thanks to recent restoration work.

On the high ground, overlooking the city, stands the Duomo, alone on a place where you would expect to find the usual castle. Instead, on the top of the Gusaco hill stands the cathedral of Saint Cyriacus, one of the most beautiful churches in the Marche region, built in the early 11th century on the site of a pagan temple, perhaps dedicated to Aphrodite Euploea, the goddess who protected sailors.

The birth of a port

The very first sailers on the Adriatic discovered that this stretch of coast was a good landing point, offering deep water and protection against the north wind. The harbour to the east of the town was originally protected only by the promontory on the north, shaped like an elbow. That is why the first settlers, the Picentes 3, called the place Ancona, which stems from the Greek word Ἀγκών (Ankòn), meaning "elbow".

A few centuries later, in 387 BC, Dorians from Syracuse, a flourishing town in Magna Graecia 4, landed on the Adriatic coast of Ancona. The Syracusan forces, attracted by the site’s geographical position and its natural defences, founded a prestigious city, which became a focal point in the strategy of expansion. The Syracusans built the first pier in the harbour and brought with them their language, rites, religion and laws, all of Greek origin. In honour of Aphrodite and Diomedes (king of Argos and mythical companion of Ulysses), they erected temples with inscriptions, whose remains can still be traced from the top of the hill to the sea, as in the still partly concealed Hellenistic necropolis. They also established a dye factory for Tyrian purple (the royal or imperial purple) in the port of Ancona.

The city had its own coinage with the bent arm holding a palm brench on one side and the head of Aphrodite on the reverse. They continued the use of the Greek language. The highly civilised features of Syracusan culture were assimilated immediately and maintained for a long time, even after the later Roman colonisation. The language, mentality and tastes in Ancona were evident signs of this assimilation, facilitated by contact with the Hellenistic world through links with Taranto, Delos, Rhodes, Alexandria, Pergamon and Athens.

Roman Ancona

Historically speaking, Ancona’s natural role as a driving force in the Adriatic, Aegean and Mediterranean areas soon became evident (even today its development still depends to some extent on the sea). When Ancona realised that the times were changing, it allied itself with powerful Rome so as to keep its supremacy in the Levant. Ancona considered the Adriatic its own sea and did not even try to cross the barrier of hills at its back or form alliances with towns that did not serve its purpose. Ancona felt itself to be different from its geographical context and was accustomed to living in isolation, to solving its troubles alone.

The alliance with Rome became a reality in 295 BC, with the battle of Sentinum. The coalition of Samnites and Gauls bravely challenged the Roman army without the help of their other allies, the Picentes, the Umbrians and the Etruscans. As a result Rome asserted its supremacy once and for all in Central Italy. According to Livy 5 Ancona was occupied as a naval station in the Illyrian War of 178 BC. Julius Caesar took possession of it immediately after crossing the Rubicon. Its harbour was of considerable importance in imperial times, as the nearest to Dalmatia. As early as the time of C. Gracchus 6 (154 BC - 121 AD) a part of its territory appears to have been assigned to Roman colonists, and subsequently Mark Antony established two legions of veterans which had served under Julius Caesar. At this time it probably acquired for the first time the rank of a Roman colony, which we find it enjoying in the time of Pliny and which is commemorated in several extant inscriptions.

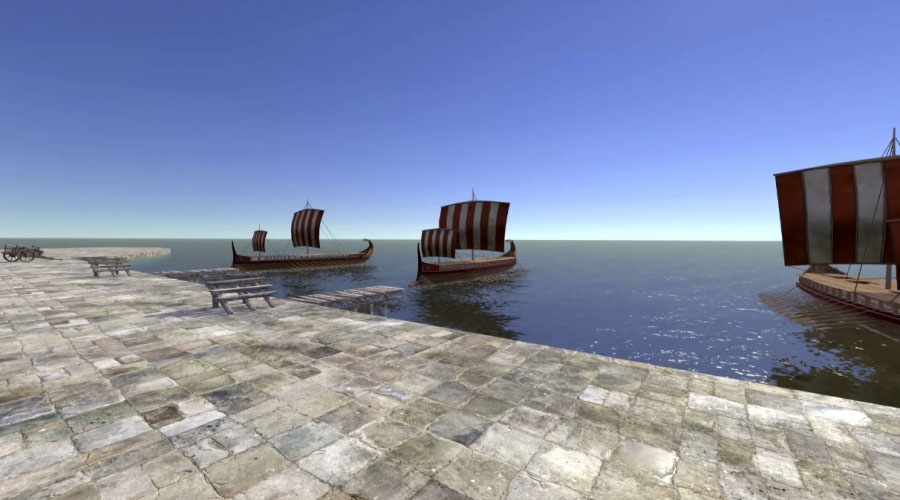

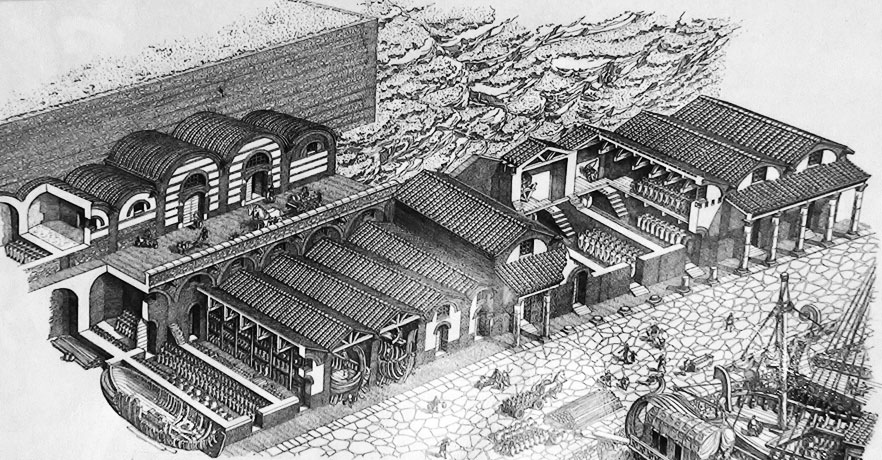

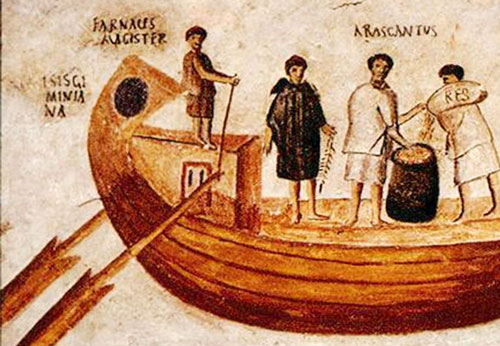

The very recent archaeological excavations on the Vanvitelli promenade have brought to light buildings dating back to periods ranging from the 4th century BC to the early Middle Ages. They can be taken as more evidence of the vitality of a port that traded with all the more developed Mediterranean countries, to the east and to the west. During the excavations, once the uppermost layer had been removed, various spaces were revealed, of different sizes according to the uses they were put on – warehouses for storing goods as they arrived or left the port, and large areas for shipbuilding activities.

Trajan, private investor

As in Centumcellae (modern Civitavecchia) the emperor Trajan considered Ancona as vital for naval and commercial use. The Roman colony of Ancona became an important link with the east, a departure point for armies directed overseas. Trajan ordered his personal architect, the Syrian Apollodorus of Damascus, to construct the north mole and to build new port facilities – the structures recently brought to light – at his own expense, pecunia sua, and also extended the mooring quays. Besides that he set up logistic centres for the housing and organisation of large numbers of soldiers. The surrounding countryside was mobilised to supply food, straw, hay and horses. The military expeditions to Dacia, Pannonia, Egypt and the Orient involved massive provisioning efforts.

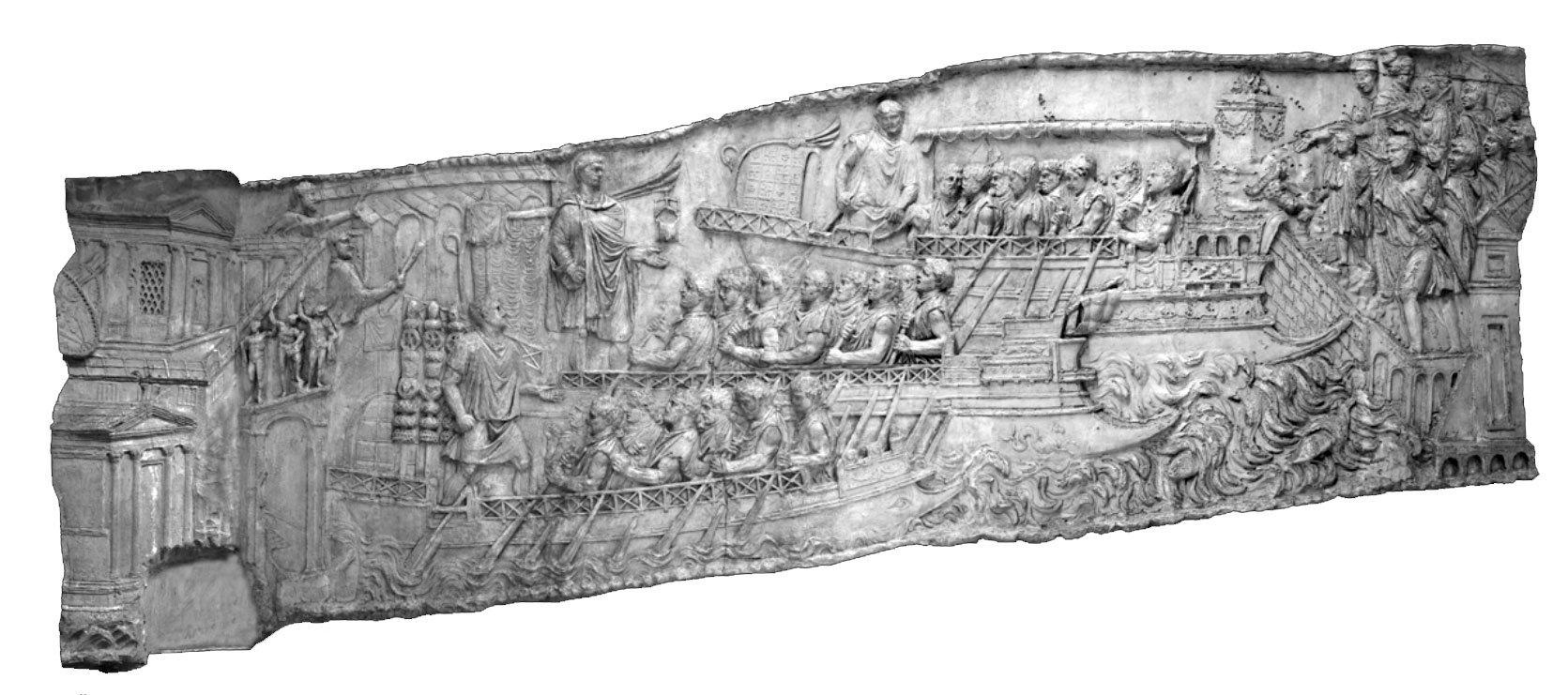

Trajan’s Column in Rome gives a figurative interpretation of the role of Ancona’s port and puts the discoveries of these recent urban excavations into context. To confirm the success of this imperial strategy, in 115 AD the Roman Senate and the people of Rome (or maybe by order of the emperor himself) dedicated one of the most important monuments in the history of Ancona to Trajan: a white, marble triumphal arch at the end of the mole. This arch too was designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, the same architect who planned Trajan’s Forum in Rome. Among the most impressive and elegant of Roman arches, it was admired by citizens and visitors alike. The arch, frankly a bit hidden from the walls, served as port protection when Ancona became a basis for the Roman fleet patrolling the Adriatic Sea. It is more slender than other Roman triumphal arches and its height was emphasized by bronze statues on its top, which have never been found, but an inscription indicates that the central statue of Trajan was flanked by those of Plotina, his wife, and Marciana, his sister. The two women were given the title of Augusta and are known to have held great influence over the emperor, in particular by favouring Hadrian's accession to the throne. In 839 AD Trajan’s Arch was sacked during a Saracen raid and the statues of the emperor, his wife Plotina and his sister Marciana were carried off (a large part of the city was also destroyed). The bronze rostra 7 in the spaces between the columns were also removed – the holes used to fix them in place are still visible.

Becoming an adult harbour city

The romanisation of Ancona, meaning its inclusion in a political, military and economic body, resulted in the functional and urban expansion of the town. The area within the city walls was doubled and Roman Ancona shows, for the first time, signs of a wider perspective – while continuing to look to the sea, it established closer links with its hinterland. Included in the Imperial road network Ancona’s influence crossed the Astagno hill and other hilly barriers to establish a link with Rome based on mutual interest, but involving subjection which has lasted until the present day. At the height of its expansion Ancona numbered 12,000 inhabitants and had an amphitheatre with 20 steps, originally capable of hosting about 11,000 spectators.

The amphitheatre was built between the end of the first century BC and the early first century AD during the reign of Octavius Augustus and later modified by Trajan. Due to historical stratification (the amphitheatre was mostly built over by medieval and later buildings) it looks today like a building site in progress.

The arena had four entrances, among them the Porta Pompae for soldiers, the Porta Libitinensis, consecrated to the goddess who presided over the passage to the afterlife, intended for those dead or wounded, and the Porta Sanavivaria for the winners and those who were pardoned. The entrance was free for the ordinary citizens and since the shows lasted several hours or even days, at times the spectators used to bring food and drink from home. The most common representations were the gladiator fights, usually carried out by prisoners or slaves, but there were also performances with wild animals and more rarely even mock naval battles. Today the Roman amphitheatre is a charming place where various performances, from music to poetry, are performed.

In the school of the gladiators is a large black and white mosaic depicting a dolphin and an inscription 8:

P(ublius) Hortorius Scauru[s - Ca]esius (?)

Sex(ti) f(ilius) IIviri d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) p(ecunia) p(ublica) [f(aciendum) c(uraverunt) i(dem)]q(ue) p(robaverunt)

The thermal baths of Ancona were situated outside the walls and served both the town and the port, an evident sign of the latter’s prosperity. The substantial investments by Roman emperors, especially Trajan, were meant to make the port of the elbow a springboard towards the Balkans during the second Dacian war, as we saw testified by the bas-relief on Trajan’s column in Rome. This base from 2,000 years ago echoes in the port. Even today Ancona still rules the Adriatic Sea, its ‘own sea’.

Sources

- Ancona looks towards the sea by Aldo Canale (Ulisse).

- http://www.lovelyancona.com.

- Notes

- 1: Photo: Ulisse.

- 2: Read also our article "Civitavecchia, historical notes".

- 3: Local population on the east coast of Italy: there is linguistic evidence that the Picentes were comprised of two different ethnicities: a group known to scholars as the "South Picenes" were an Italic tribe, while the "North Picenes" appear to have had closer links to non-Italic peoples.

- 4: Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day regions of Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria and Sicily that were extensively populated by Greek settlers.

- 5: Livy xli.i - profectus ab Aquileia consul castra ad lacum Timaui posuit; imminet mari is lacus. eodem decem nauibus C. Furius duumuir naualis uenit. aduersus Illyriorum classem creati duumuiri nauales erant, qui tuendae uiginti nauibus maris superi orae Anconam uelut cardinem haberent. Translation: The consul, departed from Aquileia, camped at lake Timavus, which lies near the sea. Thither came with ten ships the duumvir for the ships, Gaius Furius. To attack the fleet of the Illyrians two duumviri for the ships were appointed. Those of Ancona had the task to monitor the coast of the Adriatic Sea with twenty ships.

- 6: Gaius Sempronius Gracchus (154 v.Chr. - Rome 121 v.Chr.): orator and politician. At the age of twenty years he became part ot the commission that had to implement the amended legislation on land.

- 7: Naval ram.

- 8: Translation: Publius Hortorius Scaurus and Caesius, son of Sextus, mayors, arranged and approved, with public money, by decree of the city council.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.