"Roman law is the finest monument that Rome bequeathed to Western Europe. This applies not only to its content but also to the form that law has taken, as the result of a historical development in which the law of a city-state changed into that of a world empire." 1

This applies not least to Roman Maritime Law.

This website is about Roman ports and overseas trade. So it is obvious that our articles will occasionally discuss various aspects of that law. Think of the rights regarding the Annona transports2 and when a shipowner entrusted his (released or not) slave with the management of a transport3.

In early 2024, Roman Ports was approached by a former German lawyer who had written a booklet entitled Römisches Seehandelsrecht4 under the pseudonym Gaius Q. Maiorstramini. Especially for us, Mr Maiorstramini was kind enough to prepare a summary. On the basis of this summary, we have filtered the following article and (hopefully) made it comprehensible to you.

ROMAN MARITIME LAW

Importance of maritime trade in the Roman Empire

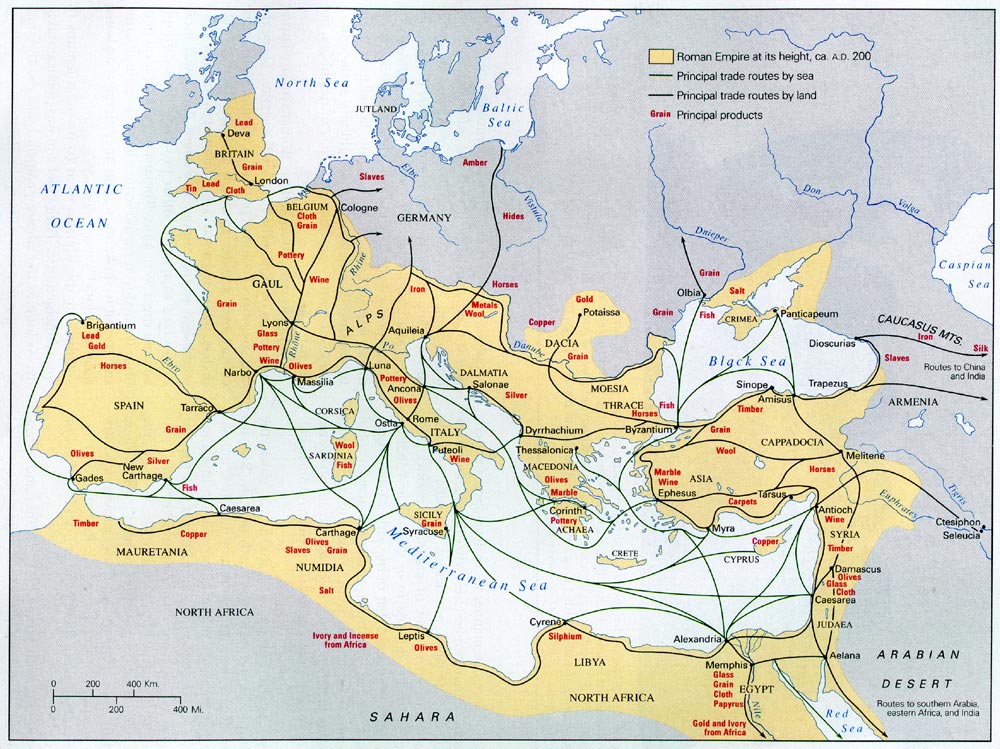

Despite the fact that the Romans, unlike, for instance, the Phoenicians, were certainly not a seafaring people, maritime trade became immensely important to the economy in Roman antiquity. They would have preferred all trade to be done over land rather than through the unpredictable, murky and dangerous waters for which the average Roman had a great fear and aversion.

During the winter months, there was even a mare closum (closed sea)6. In principle, there was no sailing then.

As the empire expanded, however, this became more and more impossible. In particular, the areas on the other side of the Mare Nostra (Our Sea), as the Romans called the Mediterranean, could supply the essential raw materials and luxury goods that Rome increasingly needed. These were often areas that were impossible or very difficult to reach by land.

Incidentally, the same applied to other countries around the Mediterranean, including the various islands, the Black Sea, and the Atlantic as far as Britain.

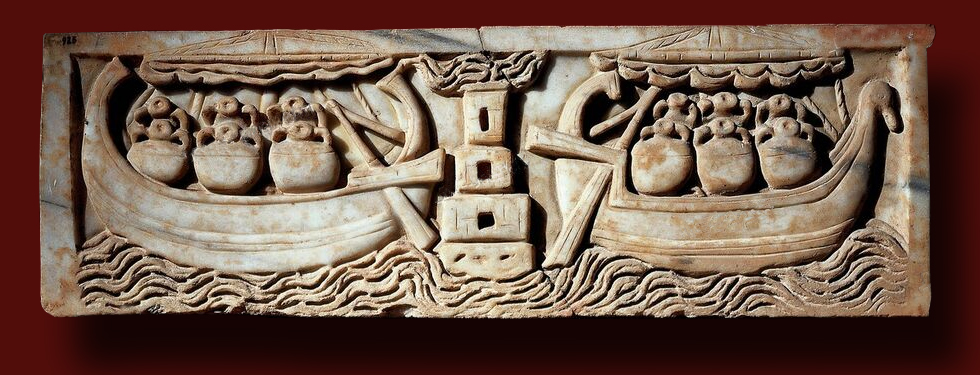

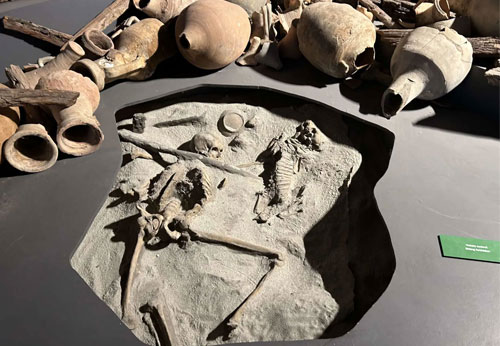

The products that Rome imported were numerous: wood for (war)shipbuilding from Lebanon, among others, and foods for the upper classes such as the fish sauce garum, wine, dates and, from Sullecthum7 and Baetica, present-day Andalusia, olives, which were not only used for culinary purposes but whose oil was also used for skin care and lighting9. The dye purple came from Tyre10.

But above all, sea trade was indispensable for the import of vital grain, as Rome could not get enough food from the surrounding areas and therefore had to secure its grain supplies, initially from Sicily and later from Egypt (annona)11. This went so far that these regions were forced to sell 10% of their annual produce to Rome to ensure the population's nutrition12. The navicularii (shipowners), who supplied the ships for importing grain, enjoyed extensive privileges: under Claudius, they were guaranteed social promotion and Nero granted them tax relief.

It has been calculated that these grain transports required between 800 and 1,000 ships a year with an average cargo capacity of 300 tonnes. Passenger transport was rare at first, but became increasingly important as the Roman population grew richer. Rich merchants even undertook pleasure trips to places of interest, officers were transferred, troops were moved to overseas battlefields and high-ranking officials undertook inspection trips to overseas provinces13.

Given the great importance of sea trade, but also the risks involved, it is obvious that the associated problems were subject to differentiated legal rules, as we know from the ancient Romans. It was even claimed that:

"shipping is related to the main business of the state""

Nevertheless, sources on Roman maritime law are scarce. Essentially, the following are regulated:

1.) the lex Rhodia de iactu, the Rhodian law on the throwing overboard of goods, in D. 14, 2;

2.) the actio exercitoria, the charge against the shipowner, in D. 14, 1;

3.) the foenus nauticum, the maritime loan debt, in D. 22, 2;

4.) the receptum liability of the shipowner in D. 4, 9.

These four topics will be dealt with here briefly.

Throwing goods overboard (lex Rhodia de iactu)

The Apostle Paul was already aware that the sea was not a safe place and suffered shipwreck three times15 and the following is recorded in the Acts of the Apostles: "And since we had terrible storms, the next day they threw cargo overboard, and the third day they single-handedly gave up the ship's rigging" 16.

These included Rhodian maritime law. It was so important that even the emperor was not above it. Someone from Nicomedia sent Emperor Antoninus the following petition and asked for his opinion: "Dear Lord Emperor Antoninus, after we were shipwrecked near Italy [or Ikaria], we were plundered by the customs tenants living in the Cycladic islands." Antoninus replied: "I may be lord of the earth, but the law is lord of the sea".

What we are dealing with here is the Rhodian law on nautical matters, the lex Rhodia de iactu, an extract of Rhodian maritime law17. Its origins, hence its name, are on Rhodes. By the end of the 3rd century BC, Rhodes held a dominant position in maritime trade in the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean.

It is assumed that Rhodian maritime law was codified customary law, a custom commonly known in Mediterranean trade as the fixed content of a maritime contract, recognised by Roman jurists and Justinian19.

Problem definition and regulations

When a ship is in distress at sea, it may be necessary to throw ballast from the ship overboard to save the ship and its remaining cargo. The question then arises whether and to what extent the owners of the goods thrown into the sea can claim compensation from the owners of the rescued goods and/or the master.

According to D. 14, 2, 1, the following applies: if goods have been ejected to save a ship from distress at sea, the damages must be compensated by contributions from all.

Content of the claim and claimant

The owners of the sacrificed goods have a claim for damages against the magister navis20 under the contract of carriage, the substance of which is disputed. It should be based partly on a lien against those liable for damages and whose goods were saved, partly on payment in case the goods were spared.

Right to compensation

The main claimants are those whose goods were sacrificed. But even if someone's goods were damaged and tarnished when part of the cargo was thrown overboard, they are entitled to compensation. This is because the jurist Papirius Fronto21 saw no difference in whether the goods (or even pearls, precious stones or valuable clothing) were lost as a result of being thrown into the sea, or whether they lost value because they were damaged as a result only. However, if the goods were not damaged as a result of being thrown into the sea, but as a result of water entering through a leak, even if it had happened at the same time, there is no claim, but an obligation to contribute.

In the case of a non liquet, i.e. failure to prove the cause of the damage to the goods left in the ship, there is no claim, but the obligation to contribute is based on the residual value remaining after the damage, not on the value, if any, in force at the port of destination.

In the case of piracy: Whoever pays money to buy the ship out of the hands of pirates has the same claims as the one whose goods were sacrificed by throwing them into the sea, but not the one who compensates for individual damages (e.g. buying looted slaves free).

Persons without goods

Even persons who have not loaded any goods on which a lien could be exercised, such as the ship's charterer and passengers who are not carrying goods but are on board purely as passengers, are obliged to bear their share of the cost of putting goods overboard if they do carry valuables.

Right of recourse (right of recourse)22

In any case, according to the contract of carriage, the magister navis has a right of recourse against the other owners whose goods were saved by putting part of the cargo overboard, which presupposes that he either satisfied the person who sacrificed his goods or transferred the right of recourse to him.

Successful action to save the ship and cargo was the linchpin of the claim. The maritime law of the lex Rhodia de iactu presupposes preservation of the ship. Therefore, damages must be borne jointly by the charterers and passengers. This did not apply if the ship is damaged in a storm without the master having made any maneuver to save the goods, i.e. even if all the goods arrive safely at the destination port.

Calculation of contribution

When distributing the loss, the value of the rescued and discarded goods must be added together. The saved goods should be recognised at their market value at the port of destination, the sacrificed goods at their value at the port of departure. The owners of the rescued goods must compensate the owners of the sacrificed goods in proportion to their value.

But not only those who had brought on board heavy goods that were saved, but also those who had brought in goods that did not weigh the ship down, such as precious stones and pearls, and the owner of the ship must contribute to the compensation; the only exception is food.

Liability for defects

Even if the claim is against the magister navis, it is not subject to any liability for defects. Instead, the deficiency must be divided among the others in the same way as the claim for damages, i.e., in proportion to the value of their goods at the port of destination.

Recovered goods that had been thrown overboard

These reduce the claim, possibly to zero, or oblige repayment of compensation received.

Beachcomber rights

These are not recognised: An item thrown overboard remains the property of the master and does not belong to the finder, as it is not considered abandoned.

Transshipment

It makes no difference whether goods are discarded to lighten the ship or, because it sinks, are transhipped to another ship. The claims remain the same.

On the other hand, if the boat with some of the rescued goods still sinks, those who had lost something in the ship cannot claim anything because the loss of the goods thrown into the sea is distributed only if the ship reaches the port safely.

The claim against a shipowner (actio exercitoria)

The actio exercitoria in particular shows how much Roman maritime law was characterised by the idea of traffic protection, which in turn can be traced back to the extraordinary importance of sea trade in terms of legal policy.

Problem and regulations

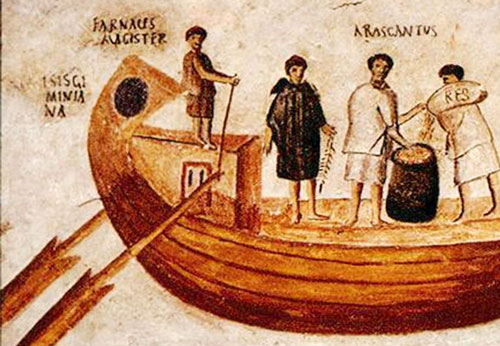

Anyone engaged in export/import business had to find a shipowner. Unlike today, however, he could not simply go to a shipowner's office, but contracts were concluded on board. Shipowners usually managed several ships, so contracts were not concluded with them, but with the magistri navis, the ship's commercial managers. However, since the trust of the charterer or another contractual partner of the shipowner, the exercitor, was put in place, it made sense to oblige him as well. Indeed, the magistri navis was usually a slave from whom nothing could be obtained because he was unable to fulfil obligations. This was done through the actio exercitoria, which made it possible to hold the owner, the exercitor, liable instead of the magister navis. In this way, Roman law came exceptionally close to direct representation, which we take for granted today, but which was alien in Roman law. The same applied when the magister navis had to deal with problems of ships or crews in a distant port.

The actio exercitoria allows a third party who has a contract with the magister navis to hold the actual shipowner, the exercitor, liable. This is the person who owns all the benefits and income from the operation of the vessel, regardless of whether he is the owner or lessee. However, the magister navis can also be held liable (adjective action). However, there is an - exclusive - right to choose between bringing an action against the executor or against the magister navis. They are not jointly and severally liable.

This liability applies to the whole, not just to the value of an existing peculium (equity), and, like the actio de peculio, coexists with the debt of the magister navis.

Joint and several liability is possible in the case of a societas, a company, in which several persons operate a ship as shipowners. The details of this are controversial.

If the shipowner is under the control of another, usually as a slave, he establishes the liability of the ruler, if he operates the shipping company with his will, in solidum (both responsible for the whole debt), otherwise only the actio de peculio. If there is a societas associated with a slave acting as exercitor, all owners are liable for the whole if he is a shipowner at their request, otherwise only the one(s) who has/have agreed.

A counterclaim by the shipowner against the counterparty does not take place. There would be exceptions in the case of grain transports.

Acting on behalf of the exercitor is not required. However, it must at least be clear from the circumstances to the third party that the magister navis is acting on behalf of a shipowner other than himself. Both slaves and free men can be magistri navis. Obligations arising from a contract with someone who is not a magister navis but, for example, a simple sailor, do not give rise to actio exercitoria. The third party is then entitled to claims against the sailor.

Multiple magistri navis

If several magistri navis are appointed, the obligations of the exercitor regarding the actio exercitoria:

- By each of them provided they are not subject to any limitation;

- In case of objective limitations (ressort principle), however, only within their jurisdiction;

- With joint power of representation only if they act together (the four-eyes principle).

The exercitor is also liable to a sub-magister appointed by his own appointed magister navis - even if this was against the will of the exercitor.

Material scope, in particular taking out a loan

The validity of the contract with the magister navis is a prerequisite for liability. Material scope depends on the pre-described power of attorney, e.g., a loan for the purchase of sails and rigging, but not for fitting (probably the prevailing view).

If the loan is misused, the risk is generally borne by the exercitor. According to one view, however, the lender should be obliged to check the plausibility of the need for money, e.g., the need to repair the vessel, if the loan has been taken out for the purpose of repair. If he does not do so, then, according to this view, he should not have an actio exercitoria jtowards the shipowner.

Either way, if no purpose was agreed when the loan was taken out and the loan was not used for the ship, this risk lies with the loan giver.

The maritime loan (foenus nauticum)

Problem definition and regulations

A maritime loan is a loan made to a merchant shipping or importing goods by sea or to a shipowner for a sea voyage.

Unlike the mutuum, the standard case of a loan, the risk of a maritime loan lay entirely with the lender. It was assumed that interest only had to be paid if the ship reached port. In other words, if the ship was lost, the owner would be released; and if it arrived safely at its destination, he had to repay a significantly higher interest of the lent amount, compared to other claims. We can therefore say that the foenus nauticum had an insurance function.

Form, risk, damages

In principle, the foenus nauticum is form-free and can therefore come about by nudum pactum (offer without consideration), but stipulatio (two-sided clause in contract) was probably the rule. Risk includes any accident, not only shipwreck, but also throwing overboard according to the lex Rhodia de iactu, piracy and other uncontrollable dangers.

Damage in this context is not only loss, but also destruction and deterioration, i.e., any impairment of the possibility of use.

Problem and regulationsg

Passengers and charterers of a ship must entrust themselves and their belongings to the shipowner when they board or are loaded onto the ship. Naturally, they must therefore be able to claim compensation if the loaded goods or other possessions become unavailable or deteriorate at the destination port. These claims are primarily against those responsible. However, it is not always possible to identify them. Moreover, it is difficult to prove their guilt, which is a prerequisite for damage claims. On the other hand, the shipper does assume that the shipowner or the magister navis will ensure the safety of his assets, especially since he has the opportunity to do so. After all, he also pays the freight for this. The law therefore considers the acceptance of objects by the shipowner as an implicit declaration to protect them from loss and damage.

However, liability is not linked to this declaration. Rather, the edict created receptum liability. The basic rule is: " If Shipowners, Leaseholders, Case Officers do not return what they have taken for someone, they will be sued". The aim was to create the trust needed to maintain and expand maritime trade with the aim of supplying Rome, as well as the provinces, with goods from overseas, which was often vital, for example in the annona, and as a result generate revenue for the suppliers, i.e., to develop the economy.

The edict presumably assumed that such a declaration had usually been made, which had subsequently led to the trade relying on it and probably created a corresponding trade custom, which the praetor (judge) applied as codified "legal law" because of the importance of sea trade to the economy of the Imperium Romanum, as described above, even if the shipper could not prove such an implied declaration. It was ultimately a matter of easing the burden of proof. It was also a matter of creating a competent and known debtor for the aggrieved party as he did not know the members of the crew or the other passengers, nor had any idea of their financial standing.

There are some parallels between receptum liability and actio exercitoria. On a ship, the options are limited. You cannot choose with which magister navis you will make the contract of carriage or other contracts relating to the ship, nor can you know in advance whether there will be theft or damage to property on the ship. For better or worse, you have to surrender yourself to the shipowner. This is the ratio legis (legal system) of both actio exercitoria and receptum liability. It governs the shipowner's liability for lost property brought by the charterer and passengers.

Property is not only deemed to have been brought aboard the vessel, but also property unloaded at the quay where the vessel was moored after the takeover agreement (the concept of manageability).

Accordingly, the carrier is liable for damage caused by loss or damage to the goods during the period from acceptance for carriage to delivery.

Reason, extent, object and scope of liability

Liability is based not only on ordinary loss, but on any kind of loss, including destruction or damage.

Culpability is irrelevant. There is pure strict liability, so there is also liability for the actions of passengers (no indemnity in this respect) and employees who are cives Romani (Roman citizens). Exclusion of liability by legal act is effective even by casus maior (severe cases) such as shipwreck, piracy, etc. The extent of liability can be up to twice the amount. The object of liability is mainly goods, possibly personal property.

Authorised and liable party

Unlike the actio exercitoria where only the obligating party is the shipowner, in the case of multiple pro rata, the authorised party is the shipper/passenger, even if a third party is the owner (third-party claim). The aggrieved party only has to provide proof of loss or damage, not of the act or person who caused the damage (facilitation of proof). Of course, the shipowner has a right of recourse against the injured party once he has satisfied the injured party.

- Sources

- - Gaius Q. Maiorstramini - Römisches Seehandelsrecht, Februar 2024 - ISBN 9783 7583 69 711

notes- 1: Definition of Roman law in the elective course 'Roman Law-Good Law' by Leiden University (Netherlands)

- 2: Read article: 'The Roman shipowners'

- 3: Read article: 'The Roman servus‘.

- 4: ISBN 9783 7583 69 711

- 5: https4.bp.blogspot.com

- 6: Read article: ’Winter shipping’.

- 7: Read article: ‘Sullecthum (Salakta)‘.

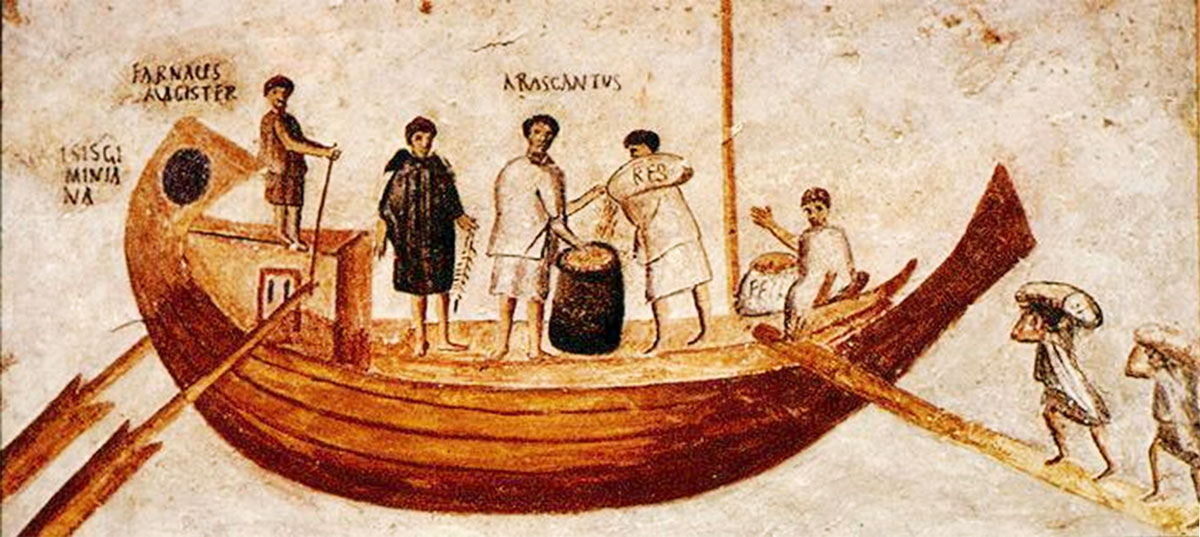

- 8: Relief: Museum für Antike Schifffahrt, Mainz.

- 9: Read article: ‘Farm the dessert to illuminate Rome‘.

- 10: Read article ‘Tyre, birtplace of Europe’.

- 11: Annual yield, harvest and annual stock of foodstuffs, especially grain.

- 12: HÖCKMANN, Antike Seefahrt, München 1985, S. 75 f.

- 13: STECKLINA, aaO (FN 12), S. 12.

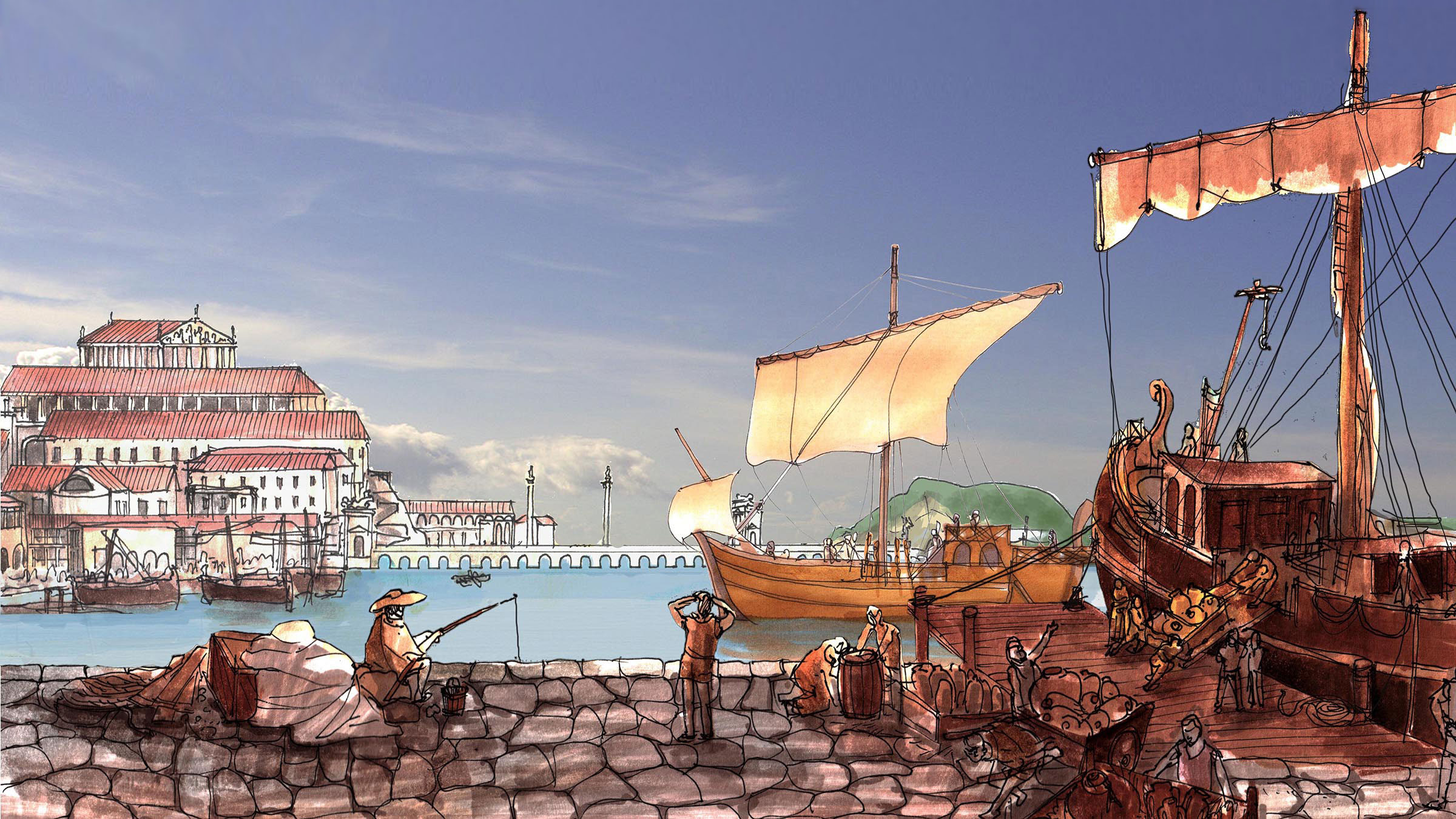

- 14: Artist's impression: Cristiano Fiorentino

- 15: II Corinthians 11, 25

- 16: Acts of the apostles 27,18

- 17: HÖCKMANN aaO (FN 14), S. 171

- 18: Artistic impression of the Colossus by Sydney Barclay (1880)

- 19: WAGNER, aaO (FN 31), S. 360.

- 20: Representative of the shipowner, when not sailing with him (the captain).

- 21: Member of the Roman gens 'Papiria', ( Jewish name Papirius) with great influence especially in Republican times.

- 22: Right of recourse - appeal to co-debtor or guarantor. Right of recourse.

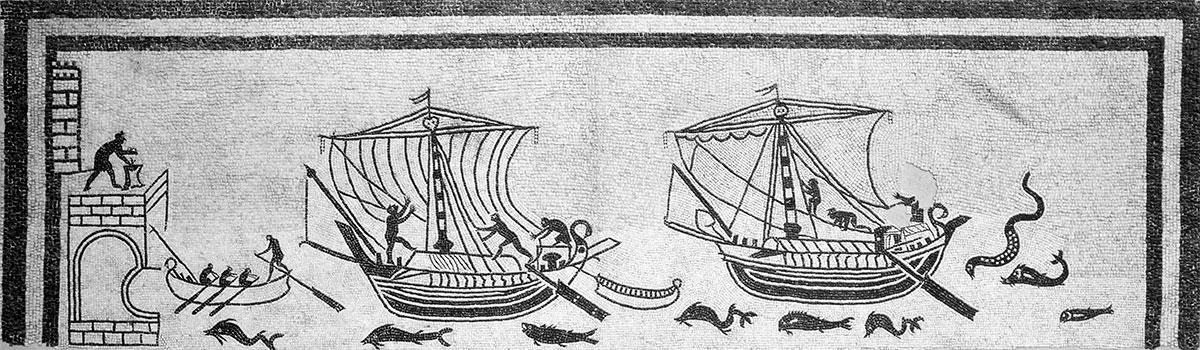

- 23: Mosaic from Veii (Isola Farnese) Today Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe in Germany. Photo: Carole Raddato

- 24: Relief from 2nd century AD (port) scene from Portus of unloading North African amphorae. At table three supervisors, one gives a guidance voucher to the dock worker, the other notes what the third person dictates.

- 25: Mozaïek in Palazzo Diotallevi te Rimini. (Photo by Frederico Ugolini).

- 26: Relief (3rd century AD) found in the Praetextat catacomb.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.