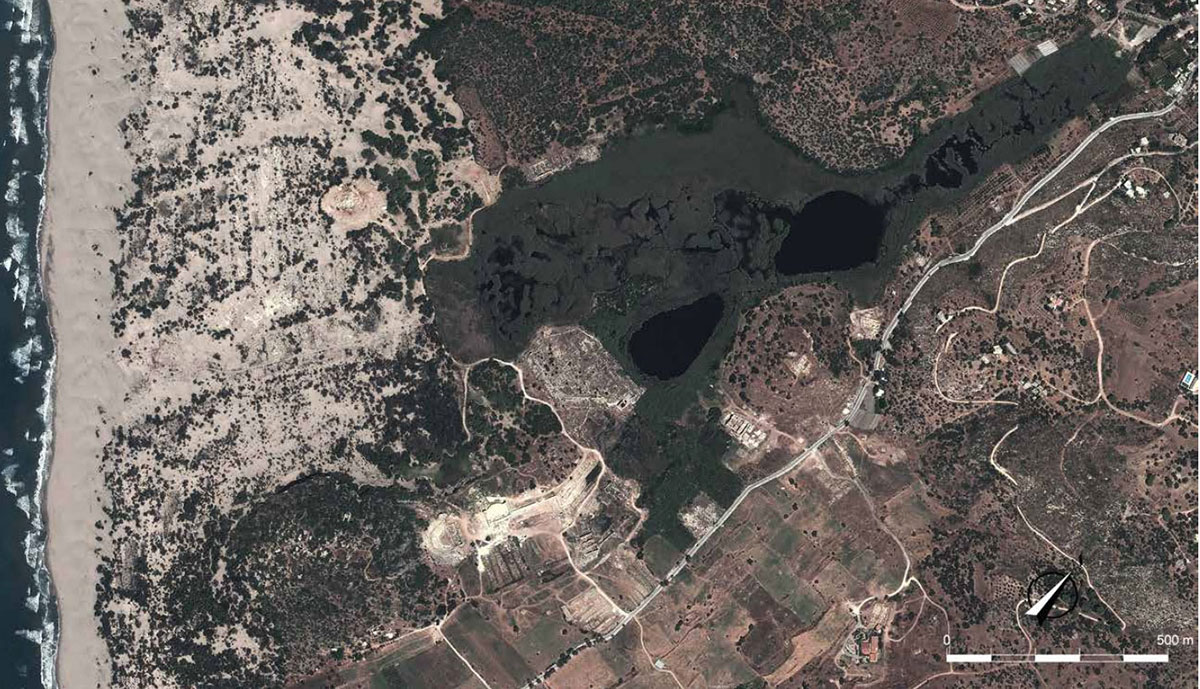

On the southwest coast of present-day Turkey is the ancient port city of Patara, the capital of the Roman province of Lycia. It was one of the four largest settlements in the Xanthos Valley and the only one in open communication with the sea, located 60 stadia2 southeast of the mouth of the Xanthos River3.

Surrounded by hills, the site possessed a natural harbour long before the arrival of the Romans, now largely silted up.

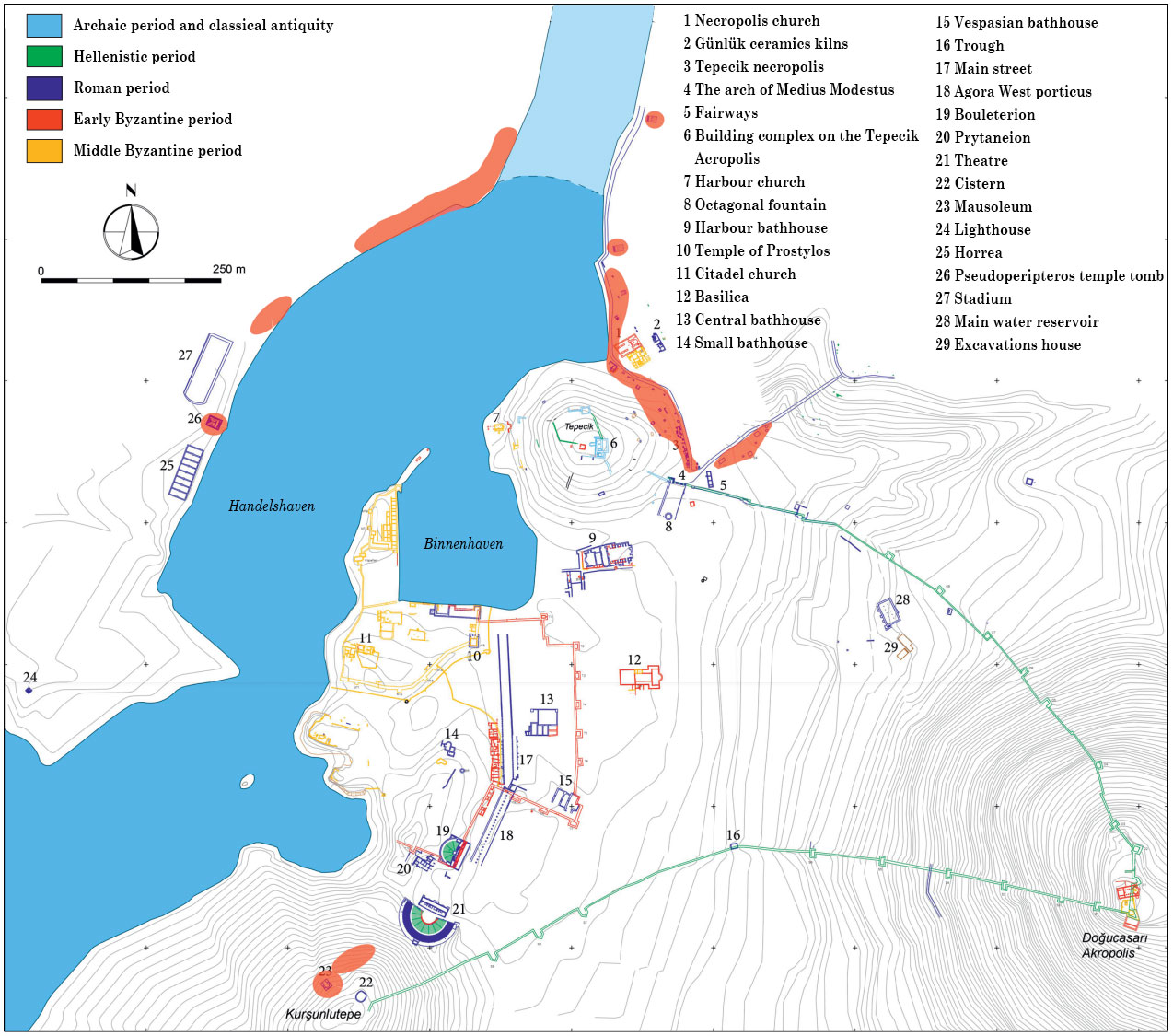

Patara is said to have been founded by Patarus, a son of Apollo4, on a hill northeast of the port called Tepecik and to have existed as early as the second millennium BC when the Hittite Kingdom ruled over much of what is now Turkey. The oldest finds date back to the third millennium BC and were excavated on the Tepecik hill.

The Hittites called the city Patar5. Incidentally, the city was mentioned by many ancient writers including: Livius6, Polybius7, Cicero8 and Plinius9. Ptolemy II called it "Arsinoe" (Strabo, 16, 3.7). Patara was therefore the main seaport of Lycia.

After several other dominions, Patara was formally annexed by the Roman Empire in 43 AD and added to Pamphylia10 (see Figure 1).

PATARA THE ROMAN PORT CITY

Meanwhile, in 176 BC, the Lycian League12 had been founded in which Patara, as the most important city had 3 votes, the highest possible number. Patara was also the capital of the League and its meeting hall, the Bouleuterion or Prytaneion, was therefore located in the parliament building in the centre of the city (Figure 8.19).

It was built in the early 1st century BC, i.e. before the annexation of the Romans, and could accommodate 1,400 people. In the centre of the cavea (tribune) was a tribunalis (raised platform for the seats of the magistrates). In the middle of the 1st century AD, the cavea was enlarged by Claudius or Nero, probably in connection with the annexation of Lycia as a Roman province.

A century later, after an earthquake in 142 AD, a porticus (covered colonnade) was added on the outside and a stage building in the hall itself as the hall was also to serve as a concert hall.

The centre of Pantara was connected to the inner harbour via Harbour Street, the widest and one of the best-preserved streets in the city (Figure 8.17). There were ionic columns on both sides of the street. Granite columns to the east and marble ones to the west.

The northern city gate, an arch of honour with three vaults, is also preserved (figure 8.4). This had been built by the citizens of Patara in 100 AD in honour of the governor of Lycia, Mettius Modestus.

THE PORT

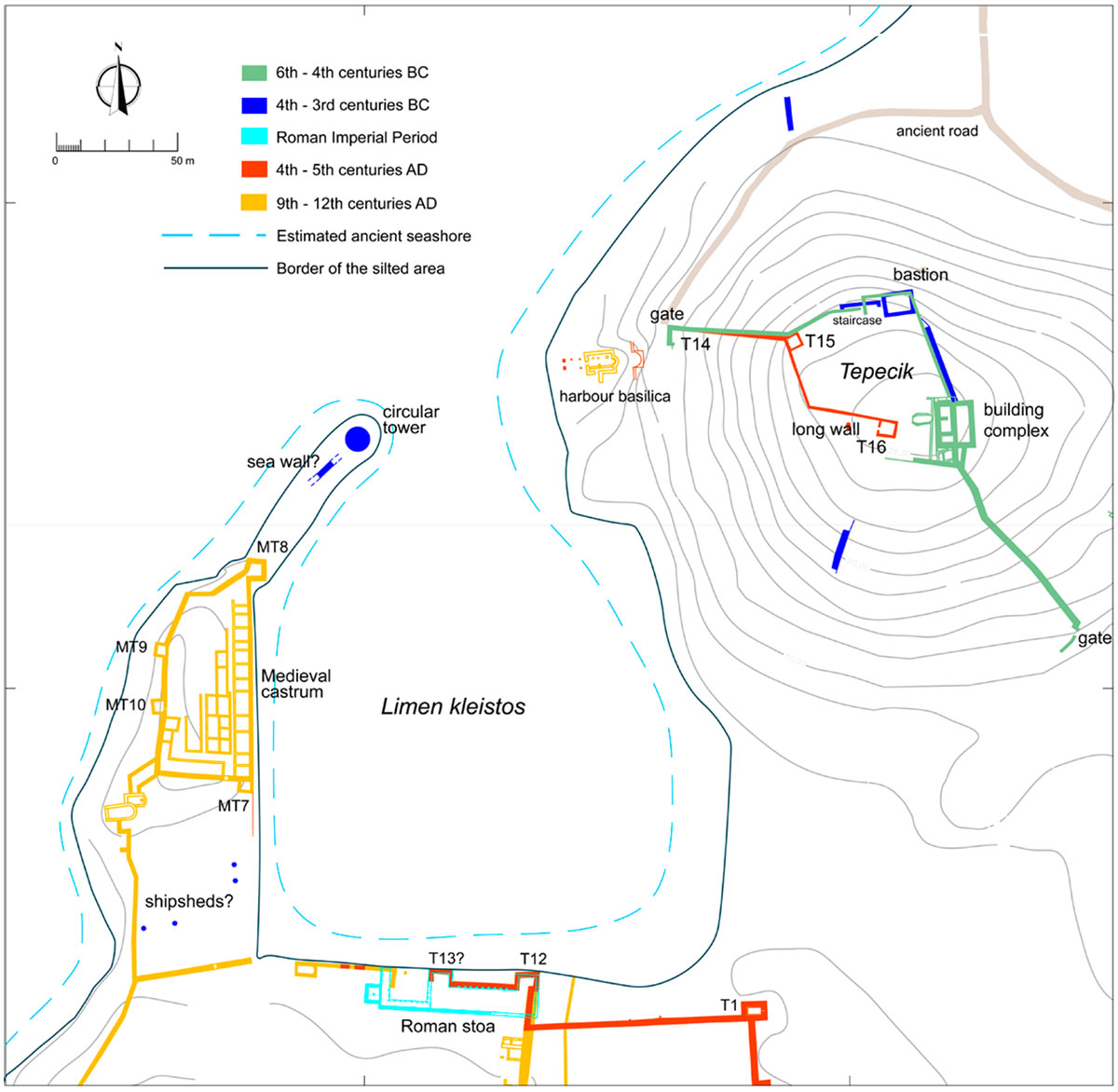

No doubt, the naturally sheltered bay will have been one of the main reasons for founding a city right here. Settlements from the early 3rd millennium BC used the natural bay as a harbour or safe anchorage. Fairly recent research has shown that there was already a so-called limen kleistos16 by the end of the 4th century BC, which was created by erecting a seawall topped by military ship sheds from the same period.

The oldest traces of defences found are on Tecepik hill. Due to its strategic location on the eastern sea routes of the Mediterranean, where sea routes to the east and west, north and south intersected, Patara became one of the important port cities of south-western Anatolia and was the gateway to the sea from the Xanthos valley in western Lycia, where major cities such as Xanthos, Pinara and Tlos were located.

The inland port of Patara was made suitable as a naval base and witnessed many battles between the leading powers in the Mediterranean. Diodorus18 mentions a number of 40 ships sent by the Lycians to the Persian navy to fight in the naval battle of Salamis in 480 BC 19.

In the centuries before the domination of the Romans, defensive walls and towers had been built several times in Patara (see Figure 6). During the long period of the Pax Romana, which lasted until about 250 AD, the colossal Roman Empire had no need for defensive walls for cities located far away from Rome on the outskirts of the empire. Moreover, over time, these walls had become very weakened and served mainly as quarries of ready-made blocks for new constructions. So although the city's military importance seems to have declined during the period of the Pax Romana, its strong logistical position in the region was maintained with the construction of the imperial lighthouse20 (figure 8.24) and Hadrian's horrea (warehouses)21 (figure 8.25).

From the third century AD, especially in Rome and Athens, people started building defensive walls again. Whether this happened or not with the ports in Asia Minor during that period is hardly known. Unfortunately, both written sources and archaeological data on this are rather meagre23.

Most building remains visible today around Patara's inner harbour date back to the Middle Ages. Patara was restored to the naval port it once was in the 10th century AD. A small area south of the inner harbour was surrounded by an early Byzantine city wall with at least four towers. Another area on the western spur of the inner harbour, measuring about 150 m long and 50 m wide, was also surrounded by walls with towers (Figure 6: MT 7 to 10). According to researchers Bruer and Kunze24, this section, with buildings constructed according to an orthogonal plan, was a castrum (Roman army camp). This castrum, which would have housed the soldiers of the Byzantine navy, overlooked both the bay (the trading port) to the west and the inner harbour to the east.

Later, however, due to the accumulation of silt carried by the Xanthos River, located about 5 km west of the bay, the harbour gradually silted up and from the end of the 14th century AD turned into a swamp.

The harbour and most of the city were abandoned by the middle of the 15th century25.

THE HORREA OF PATARA

Back to the good old days before the harbour silted up. Patara's outer harbour was apparently intended as a commercial port from the beginning of its existence and was estimated to be 1.6 km long and 400 metres wide. Little or nothing is documented about the facilities at the commercial port. Were there mooring quays or did the ships anchor and the cargo, was it brought ashore by smaller ships? Where were the loading offices and storage sheds located? The site where these facilities should have been lies now under a thick swamp layer that is barely penetrable. Consequently, much in-depth research has never taken place. Only one tangible evidence of a harbour structure has been found, identified as a horrea (warehouse complex) in particular by the following Latin inscription on the harbour side:

HORREA IMP . CAESARIS DIVI TRAIANI PARTHICI F . DIVI [NERVAE NEPOTIS TRAIANI HADRIANI AUGUSTI

(Horrea of the commander-in-chief caesar, son of the divine Traian who defeated the Parthians, grandson of the divine Nerva, Trajan Hadrian Augustus).

The remains of this complex, which according to the text was built by Hadrian, probably on his visit to Patara in 131 AD, are located along the western bank of the trading port, right next to the lighthouse that indicated the entrance to the port.

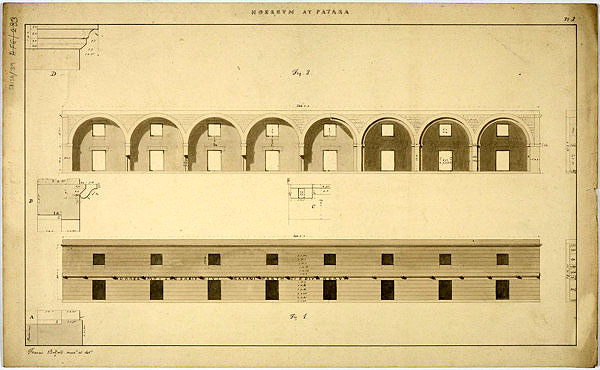

The Austrian researcher R. Nieuwman described the horrea at the end of the 19th century, noting even then that the roof and vaults had disappeared already and that the building had the dimensions of 70 x 27 metres28. French researchers estimated the useful area at 1,422 m2. The building was preserved to a height of 7.90 meter.

The complex was divided into eight rooms of equal size by walls running parallel to the short side of the building complex. Due to the presence of pilasters in the side walls of the rooms, it is assumed that these rooms were covered with barrel vaults reinforced in the middle by double arches. From the outside, each room had its own entrance of about 2 m wide on the facade. Inside, no evidence of a second floor has been found although there was a square window above each door suggesting a second floor.

The inscriptions leave no doubt about the function of the buildings: they were indeed warehouses. Although early travelers identified the horrea as granarium29, however, there is nothing in their plan or layout that proves that these warehouses were exclusively for the storage of grain. Incidentally, it is the common opinion that these horrea were used for the annone30 during the Roman empire and related to the delivery of wheat from Egypt to Rome.

Erkan Dündar and Mustafa Koçak write that in those days Patara had no hinterland of its own to supply agricultural products. Perhaps we should therefore see Patara as a transit port where ships mainly docked to forage or shelter from the weather and was the horrea used for other products. The question then remains why the grain from Alexandria, destined for Rome, would be stored in Patara? Or was it perhaps that a small portion, destined for the region, remained behind in Hadrian's horrea? Perhaps follow-up research could provide a definitive answer to this one day.

THE MARITIME TRADE OF ROMAN PATARA

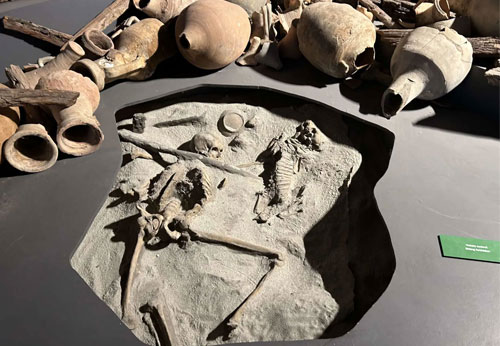

Based on amphorae finds from various regions, we can retrace which regions Pantara traded with. Archaeological finds show that it was an important hub in maritime trade between the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. During the Roman imperial period, Patara became the capital of the province of Lycia (shortly afterwards even of Lycia and Pamphylia) and acquired a higher commercial and political status than the military status it had previously enjoyed. Especially after the annexation of Lycia as a Roman province by Emperor Claudius in 43 AD, Patara began to maintain commercial links with distant manufacturing centres.

As in Hellenistic times, Patara remained mainly linked to trade in the Aegean. However, Patara now supplemented this trade with imports and exports from Cilicia, Palestine and Egypt in the east, and Thyrrhenia, Narbonensis, Baetica, Lusitania, Mauretania Caesariensis, Tripolitania and North Africa in the west.

However, partly due to the lack of any fully excavated port structure, few studies have been done on overseas trade. Very little research was also known about the large numbers of amphorae found at Patara. Therefore, archaeological work in this area has been greatly intensified since 2006. Currently, more than 10,000 fragments of amphorae from the Roman imperial period have been identified and classified, including commercial jars from 34 different regions and urban production centres.

Most of the 1st-century AD amphorae recovered at Patara came from Knidos, a Greek port city in Asia Minor. This is followed by numbers of amphorae from Rhodes, Egypt, Italian Brindisi and the eastern Mediterranean region. Several Italian amphorae from the first century AD found in Patara indicate that Italy began to play an important role in maritime trade with Patara.

For products from Egypt in particular, including grain, travelling via Patara was the best and shortest route.

THE LIGHTHOUSE

To demonstrate the enormous potential of the Patara harbours, looking at the buildings with their various functions that escaped drowning under the swamp and can still be seen today, and which were all involved with the harbour in one way or another, directly or indirectly, should be sufficient.

One of the most important of these buildings is undoubtedly the base of a lighthouse excavated from under the sand, which, 27 metres high, from a rock, cast its light over the eastern Mediterranean.

The lighthouse was built by Emperor Nero around 65 AD under the supervision of then governor Sextus Marcius Priscus33.

The lighthouse, which was completely destroyed by a tsunami in 1481, is currently being rebuilt with as many original, recovered, stones as possible.

A monumental inscription at the top was also returned to its original place on 13 August 2022.

The Greek inscription was at the top of the gable, on the east side as a gold-finished bronze text in Ancient Greek. The letters of the top line, the important salutation, were larger than the other lines:

ΝEΡΩΝ ΚΛΑYΔIΟΣ ΘΕΟY ΚΛΑΥΔIΟΥ ΥIOΣ

("Nero Claudius Caesar, son of the divine Claudius, grandson.....")

The rest of the translation reads: "....... of Tiberius Caesar Augustus and Germanicus Caesar, great-grandson of the divine Augustus, eleventh-time holder of the tribunal, fourth-time consul, the ruler of land and sea and father of this country, had this lighthouse built for the safety of sailors. Sextus Marcius Priscus, the imperial governor at propraetorial level35 led the construction."

Meanwhile, an inscription was also found on the pedestal of the lighthouse: "The Council and the People of Patara honour Sextus Marcius Priscus, our saviour and benefactor, propreator governor on behalf of the emperors Tiberius Caesar, Caesar and Caesar Augustus Vespasianus for years of righteous governance of the Lyceans without corruption, decorating our city with beautiful buildings, and building the Pharos and Antipharos for the safety of sailors."

This inscription shows that there was also a lighthouse on the other side of the harbour entrance, the Antipharos.

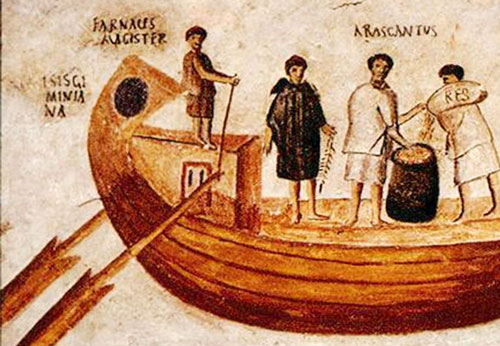

PATARA AS IN BETWEEN PORT

We already mentioned Patara as a crucial port in the eastern Mediterranean where shipping routes from all corners of the world crossed. For products from Egypt destined for Rome in particular, including grain, the journey via Rhodes or Patara was the shortest and thus the best route.

After leaving Alexandria, Patara was the first port to forage, shelter from bad weather or possibly wait for favourable winds.

To find and enter Patara safely, the lighthouse(s) played an important role.

Off the coast of Lycia is Yilan Island, which a ship had to sail past far enough before the lighthouse came into sight. Once you could see the light, sailing towards the coast wasn’t a problem anymore. From the west, the lighthouse could be easily seen from afar without obstacles. So the port, as evidenced by the many amphorae found, was not only used as a transit port. Goods were also imported for the local population, not to mention to supply the Roman garrisons stationed here in the eastern part of the Roman Empire.

In addition, especially in the second century AD, there was extraordinarily high industrial production in Patara and a lively trade of products from all over Lycia and other countries. Besides grain, these included wines and olives36. Murex turunculus37, saffron, tar and fish38 are mentioned as luxury products.

We also know from literary sources that there was a lively transport of travellers. Were these originally visitors to the oracle of Apollo, in Byzantine times it was the pilgrimage to the birthplace of Saint Nicholas (Patara 270 AD)40

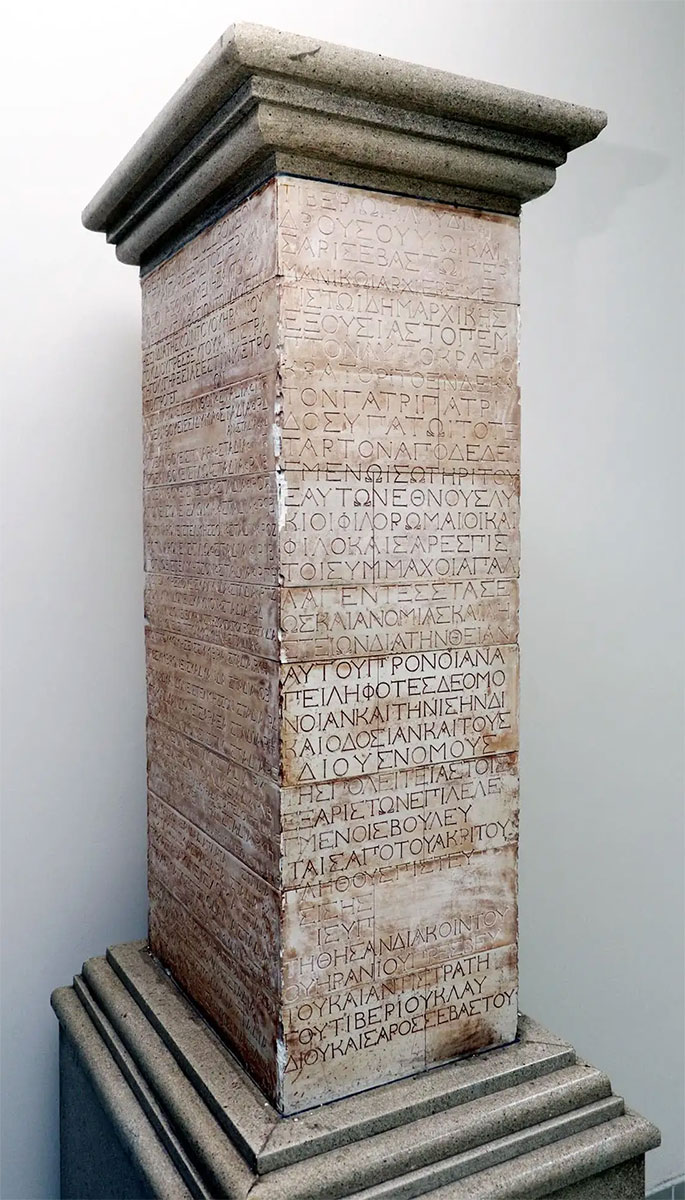

Illustrative of the city's international orientation was the monument on the quay of the harbour, a road map of Lycia for arriving foreigners, the stadiasmus patarensis. In 1993, after a fire in Patara, several described stone blocks were found that appeared to belong to a monument attributed to emperor Claudius around 45 AD. The whole formed a column with a height of 1.80 - 2 metres, inscribed in ancient Greek on three sides.

On the front was a dedication to Claudius and on both sides was an official list of the roads built by the governor Quintus Veranius in the province of Lycia. The dedication to Claudius read as follows:

Τιβερίωι Κλαυδίωι Δρούσου υἱῶι Καίσαρι Σεβαστῶι Γερμανικῶι, ἀρχιερεῖ μεγίστωι, δημαρχικῆς ἐξουσίας τὸ πέμπτον, αὐτοκράτορι τὸ ἑνδέκατον, πατρὶ πατρίδος, ὑπάτωι τὸ τέταρτον ἀποδεδειγμένωι, σωτῆρι τοῦ ἑαυτῶν ἔθνους, Λύκιοι φιλορώμαιοι καὶ φιλο¬καίσαρες πιστοὶ σύμμαχοι ἀπαλλαγέντες στάσεως καὶ ἀνομίας καί λῃστειῶν διὰ τὴν θείαν αὐτοῦ πρόνοιαν, ἀπειληφότες δὲ ὁμόνοιαν καὶ τὴν ἴσην δικαιοδοσίαν καὶ τοὺς πατρίους νόμους, τῆς πολειτείας τοῖς ἐξ ἀρίστων ἐπιλελεγμένοις βουλευταῖς ἀπὸ τοῦ ἀκρίτου πλήθους πιστευθείσης, δι’ ὃ τῆς πατρίδος ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ ἐπεκρατήθησαν διὰ Κοΐντου Οὐηρα¬νίου πρεσβευτοῦ καὶ ἀντιστρατήγου Τιβερίου Κλαυδίου Καίσαρος Σεβαστοῦ.42

This article was compiled by Gerard Huissen. Special thanks to Benoit Chamuleau who drew our attention to this important port and then provided us with input and photo material.

- Sources

- - Erkan Dündar and Mustafa Koçak - Patara’s Harbour: new evidence and indications with an overview of the sequence of harbor-related defence systems.

- - Wikipedia

- - Laurence Cavalier - Horrea d’andriakè et patara : un nouveau type d’édifice fonctionnel en lycie à l’époque impériale.

- - Erkan Dündar - The Maritime Trade of Roman Patara. Preliminary Remarks on the Amphorae.

- - Dailysabah with DHA – Lighthouse of Antalyas ancient Patara to give light again.

- - Arthur de Graauw – AncientPortsantiqes.com

- - Mustafa Koçak - A survey of the Patara harbor bay: a general overview.

Notes- 1: Caliniuc since Putzger & Westermann atlases (Atlas zur Weltgeschichte, Stier, H.E., dir., 1985)

- 2: One stadium (singular) is an originally Greek measure of about 160 metres.

- 3: Todays Koca Çayı rivier.

- 4: Butler, Alban (1798), The Lives of the Primitive Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, vol. II, J. Moir, p. 180, retrieved 2021-08-14

- 5: King Tudhaliya IV (1236-1210 BC).

- 6: Livy, xxxiii. 41, xxxvii. 15-17, xxxviii. 39

- 7: Polybius xxii. 26

- 8: Cicero p. Flacc. 32

- 9: Plinius ii.112, v.

- 10: Area in southern Asia Minor between Lycia and Cilicia.

- 11: Erkan Dündar and Mustafa Koçak: Patara’s Harbour-New evidence and indications with an overview of the sequence of harbour-related defence systems (2020).

- 12: Lycian league - alliance of independent city-states; the first democratic union in history.

- 13: Photo: Wikipedia - Dosseman

- 14: Photo: Wikipedia - William Neuheise

- 15: Photo: Wikipedia - Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

- 16: Greek -artificially enclosed inner harbour

- 17: Graphic: Patara Excavation Archive

- 18: Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC)- Greek historian

- 19: Diod. Sic. 11.3.7

- 20: İşkan, 2019: 302-317

- 21: Koçak, 2016b: 87-92

- 22: Photo: Patara Excavation Archive

- 23: Schmidts, 2019

- 24: Bruer and Kunze 2010: 87

- 25: Öner, 1999; Duggan, 2010; İşkan and Koçak, 2014

- 26: Photo: Patara Excavation Archive

- 27: Photo: Wikipedia – Dosseman

- 28: O. Benndorf et G. Niemann, Reisen im südwestlichen Kleinasien I : Reisen in Lykien und Karien I, 1884.

- 29: TAM II, 153.

- 30: Imperial food supply to the people of Rome.

- 31: Photo: Slowtravel

- 32: Photo: Patara Excavation Archive9

- 33: IŞKAN – ECK – ENGELMANN 2008

- 34: Propraetor = former praetor who acted in a provincia pro praetor

- 35: Photo: IDSB.tmgrup.com

- 36: ŞAHIN, FEYZULLAH; AKTAŞ, ŞEVKET, Urban change in Patara, in İŞKAN (2019), p.171

- 37: Snail for production of indigo blue/purple.

- 38: ÇEVIK (2021), pp.121-142

- 39: Photo: Arkeonews

- 40: ZIMMERMAN, KLAUS, History of Patara / II. Lycia under the Roman empire and in late Antiquity, in HAVVA İŞKAN (RED.) (2019), p.86

- 41: Photo: 140journos.com

- 42: Translation dedication to Claudius: "To Tiberius Claudius, son of Drusus, Caesar Augustus Germanicus, pontifex maximus, trib. pot. V, imp. XI, p. p., cos. IV design(atus), the saviour of their nation, the Lycians, Rome- and Caesar-loving, loyal, ally, freed from factionalism, lawlessness and banditry by his divine foresight, with restoration of unity, fair justice and ancestral laws, since the leadership of the state has been entrusted to councillors chosen from among the best of the people, and recalled from the incompetent majority, and by this means they (Lycians) have been given possession of the homeland by him (Claudius) through Quintus Veranius, legatus propraetore of Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus".

- 43: Photo: Wikipedia - Dosseman

- 44: Photo: Wikipedia - Alexey Komarov

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.