A [NCO] MAR[CIO] REG[I] QUART[O A R[OMUL[O] QUI A[B URBE[C]ONDIT [A PRI] MUM COLON[IAM ] DEDUX[IT]

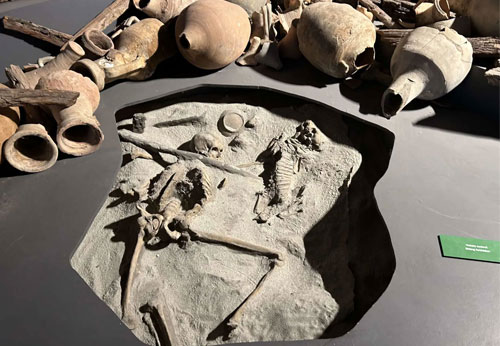

This inscription reflects an old tradition going back at least as early as the end of the third century BC, namely that the first colony of Rome was built by the fourth king of Rome, Ancus Marcius. According to the oldest description from the historian Quintus Ennius it was built as a marine base against attacks from sea during the war with Hannibal, the Punic Wars. Another Roman historian, Livy3, tells us that the base was built for the protection of the salt-beds nearby. Although written evidence is missing, archeological research in the Castrum (fort) has shown that there was already a military defensive position here in the fourth or early third century BC4. Soon, many other people such as craftsmen and merchants offered their services and established themselves at the Castrum and thus, a city was born.

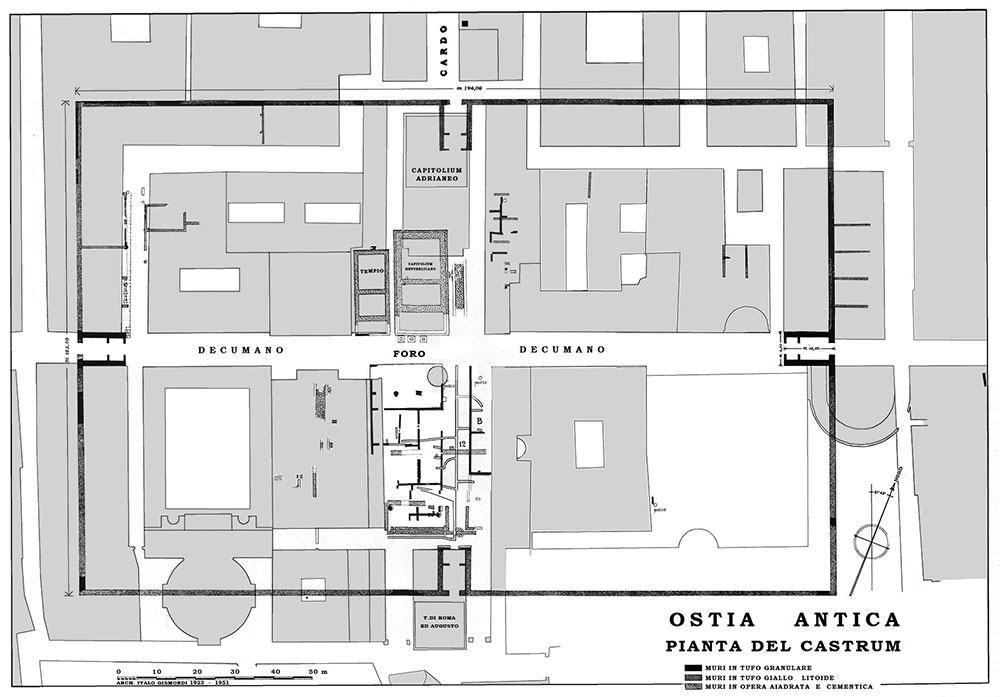

The basic structure of the Castrum can still be seen today.

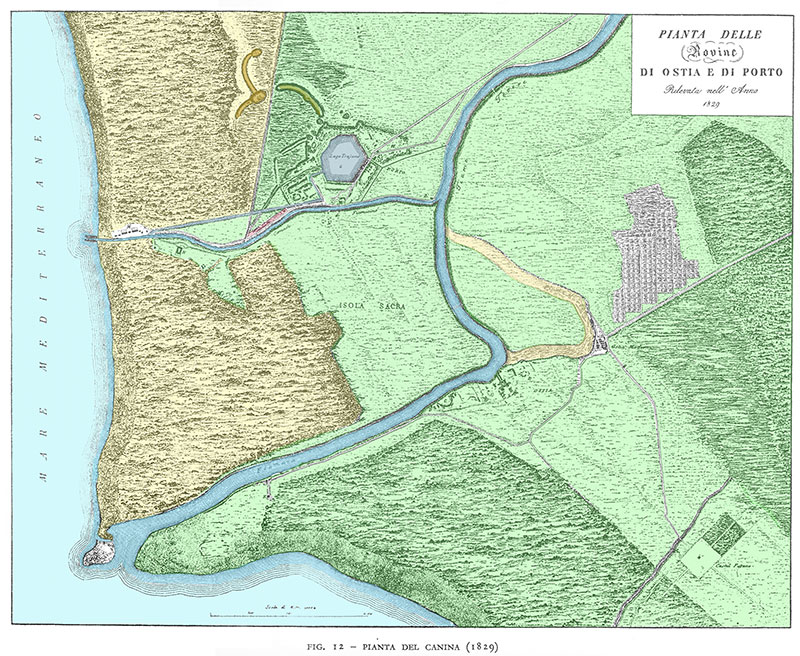

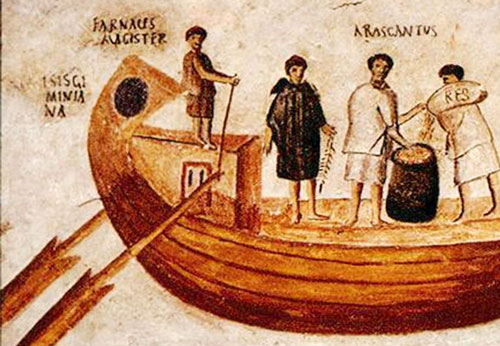

Every Roman castrum was built according to the same principal; a rectangular earthen wall (at Ostia, later remade in tufa) with a gate in the middle of each wall. The gates were connected by roads perpendicular to each other: the road between the gates in the short walls by the Decumanus Maximus, and the other by the Cardo Maximus. The two roads remain in use today. The Decumanus Maximus led at the eastern gate to the Porta Romana, the road to Rome, today known as the Via Ostiensis. From about the fourth century BC on, Ostia became very important to Roman commerce, especially for the overseas trade in grain. As Rome expanded during the empire, Ostia too, expanded. However, this process also posed a problem in that Ostia could no longer meet the huge needs of the world city. Besides that, the harbor at Ostia was silting and became very dangerous due to its open position and yearly storms. The historian Strabo5 described the situation as follows: “Ostia (was without a harbor) on account of the silting up which is caused by the Tiber, since the river is fed by numerous small streams. Now although it means danger for the merchant ships to anchor far out in the surge, still the prospect of gain prevails; and in fact the plentiful supply of tenders which receive the cargoes and bring back others in exchange makes it also possible for the ships to sail away quickly before they touch the river, or else, being partly relieved of their cargoes, they sail into the Tiber and run inland as far as Rome.” An additional problem was the increasing size of the ships, as the Tiber at Ostia was only 100 meter wide. This became a significant problem, particularly during the shipping of the overseas grain harvest. According to Plutarch6, Julius Caesar had been the first to think seriously of building moles as an enclosure and of dredging the hidden shoals and anchorages to match the great volume of shipping. Suetonius7 speaks from ‘portum Ostiensem...a Divo Iulio saepius destinatum ac propter difficultatem omissum’. Finally, the emperor Claudius began building a completely new port, a little bit north of Ostia and provided her with the promised moles. Later, during the reign of the emperor Trajan, this harbor also became inadequate and Trajan extended the harbor of Claudius by creating a hexagonal inland harbor and a canal connecting the Tiber with the sea, called the Fosso Traiano. In this way, an artificial island was created between the Tiber, the canal and the sea. This island subsequently became known as Isola Sacra, Holy Island. (See our next edition for more information on Isola Sacra.)

- Notes:

- Source: R. Meiggs; Roman Ostia; Oxford At the Clarendon Press 1973

- (1). S 4338

- (2) Ennius, Ann, ii, fr. 22 (Vahlen)

- (3) Livy i,33.9: ‘silva Maesia Veientibus adempta, usque ad mare imperium prolatum et in ore Tiberis Ostia urbs condita, salinae circa factae.'

- (4) A. Martin. "Un saggio sulle mura del castrum di Ostia (Reg. I, ins.x, 3)," in A. G. Zevi and A. Claridge (eds.), 'Roman Ostia' Revisited. Archaeological and Historical Papers in Memory of Russell Meiggs. British School at Rome, London. 1996. 19-38.

- (5) Strabo, 231-2

- (6) Plutarch: Caes. 58. 10 (7) Suetonius, Claudius 20.1

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.