By Ahmed Fergiani

Introduction

In his Res Rustica1, Columella writes: Olea prima omnium arborum est which means: the olive is the first of all trees.

In Roman Tripolitania, the land of the three cities, which comprises the cities of Leptis Magna, Oea and Sabratha in western Libya, the cash cow was the production of the olive oil since the Phoenician era, a millennium before the birth of Jesus Christ.

oil presses.

When Caesar had to fine Leptis Magna after defeating Pompey in the Roman civil war, he demanded no less than three million pounds of olive oil as a tax, a sum that lead us to raise many questions today: “Who planted and collected those olives in that area? How much of the olive oil was imported to Rome? What were the Romans doing with the olive oil two millenniums ago?”

To discuss those questions, this time I’m going to take you to several places to get a broader idea about agriculture, trade and the Roman ports in general.

First of all we go back to my homeland, a few kilometers away from the famous Roman port city of Leptis Magna. Next we’re going to Ostia and Monte Testaccio2 in Rome where I have been residing for the last ten years.

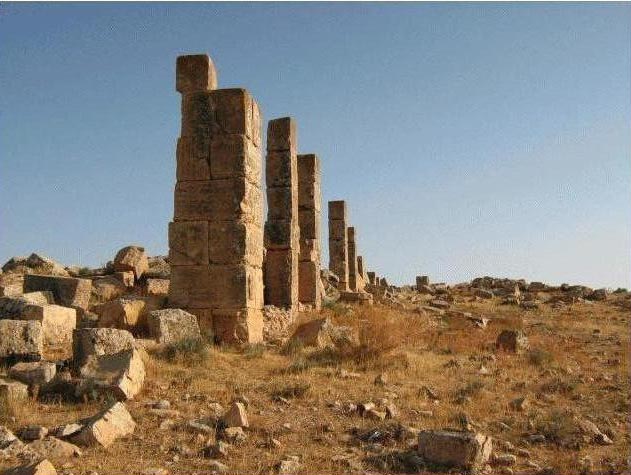

Limes Tripolitanus

As the relationship between the Romans, living on the North African coastal strip of today’s Libya, and the local indigenous inhabitants called the Garamantes, deteriorated in the mid third century A.D, the Romans built a defensive boarder, called Limes Tripolitanus. Similar to the Hadrian wall in Britain, those Limes were, in this case, initiated and expanded under the Roman emperor, who was originally from Leptis Magna: Septimius Severus.

Several defensive forts and fortified farms were built in Tripolitania in western Libya, including Garbia and Golaia (the actual Bu Ngem in the vicinity of Misurata 200km east of Tripoli), in order to protect the province from the raids of local tribes.

The population living in that Roman frontier was described as Libyphoenician and this is corroborated by a wealth of epigraphic and literary material2.

In the second century AD, the Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis3 described in his Apologia4 the landholding elite of Oea (modern Tripoli) as heavily Punicised. Many of them owned multiple estates, scattered throughout Oea's territory and controlled for them by bailiffs or slaves.

From today’s archeological remains we can confirm that former Roman soldiers were settled in this area and mixed up with those local inhabitants where the arid land was developed, dams and cisterns were built in the different Wadis (outside the rainy season dry rivers). The area has sufficient rainfall, but it is highly unpredictable and irregular. However, when the wadis have dams and dikes, the water can be regulated and the area can be developed for agricultural purposes where water management was vital to guarantee a sufficient production of cereals, figs, vines, olives, almonds, dates, and olive oil.

Today the whole hinterland of Leptis Magna is full of remains of those fortified farms called Centenaria. The British archeologist Goodchild discovered more than two hundred olive presses in the area of Tarhuna in the hinterland of Leptis Magna.

Literary references to third century ‘donations’ of oil towards the oil dole at Rome confirm the scale of export6. Part of it should be consumed in the big city of Leptis Magna but most of it was shipped to Rome through Leptis port which was enlarged by Septimius Severus.

Olive oil in Rome

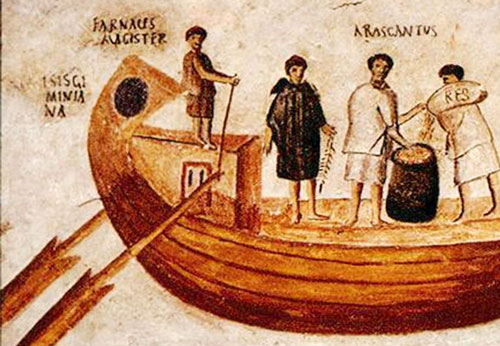

Once the olive oil from the pre-desert area of western Libya reached Ostia, the commercial hub of Rome, part of it was kept in Ostia but most of it was ferried from Ostia to Rome. Barges full of Amphorae sailed up the Tiber river to the city harbor of Rome.

There the oil was decanted into containers and the amphorae were abandoned at the harbour creating the nearby famous Monte Testaccio or the hill of the broken amphorae, which we can still visit today.

Monte Testaccio is irrefutable proof of the quantity of oil that came into Rome from North Africa and Spain. The amphorae in Monte Testaccio must have been deemed unsuitable for reuse as ventilation shafts or water pipes because the oil was seeped into the porous shell of the containers and became rancid.

Olive oil was mainly used for lighting due to its lower water content. One litre of oil produces about 134 hours of light. So if you lit a lamb for an hour in ancient Rome, you needed roughly three litres of oil per year, which means that a city like Rome, with one million of inhabitants, mostly living in Insulae or tiny crowded flats, needed more than three million litres of olive oil per year. This was big business in those days and thanks to the reforms of the emperor Diocletian in his final attempt to control the inflation and poverty in the Empire. One Sextarius olive oil, which is slightly equivalent to half a litre, would cost between 24 and 40 Dinarii depending on the quality as we are told by some archeological finds. One could say that African olive oil illuminated the Urbs Aeterna.

The olive oil was also used in the Roman baths or Thermae where Romans used it to clean their bodies after physical exercises. They smeared it on, so that it collected dirt and sweat and then they scraped it off using a metal instrument called a Strigilis.

Supply and demand was the motor that drove this trade and the decisions of the people. While the demand for oil might have risen in Rome, farmers in the outskirts of Leptis Magna only knew for what price they sold the oil and how much profit they gained. This means that such a trade was a kind of gambling sometimes. There was a distance and time between merchants and their agents, making the coordination of buying and selling difficult to manage. Merchants could not ascertain quickly when the price of oil in Africa, or Rome might be high or low, or even if their ship had sunk in a storm. But nevertheless, the Mediterranean Sea was the center of the Roman Empire. It was far cheaper to Ship oil by sea, despite the mentioned issues, than over land in those times. The trade of olive oil between Rome (modern Italy) and the North African area is today, sadly enough, far less than the 3 million litres per year from two millennia ago."

- notes:

- 1: Lucius, Junius, Moderatus Columella; (4 -circa 70 AD). Roman writer on agricultura. Res Rustica V, 8, 1

- 2: Mattingly 1986

- 3: Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis was a Numidian writer and rhetorian living in the Roman Empite between 124 and 170 AD

- 4: Apologia (Apulei Platonici pro se de magia) is the version of the defense presented in Sabratha, in 158-159, before the proconsul Claudius Maximus, by Apuleius accused of the crime of magic.

- 5: Photo 3: Jona Lendering

- 6:Historia Augusta, Severus, 18.3. Tripolim, unde oriundus erat, contusis bellicosissimis gentibus securissimam reddidit, ac populo Romano diurnum oleum gratuitum et fecundissimum in aeternum donavit.

Translation: He freed Tripolis, the region of his birth, from fear of attack by crushing sundry warlike tribes. And he bestowed upon the Roman people, without cost, a most generous daily allowance of oil in perpetuity. - 7: Photo 4: Anthonie J. Askew

- 8: Photo 6: IMAGO The Roman society centanary image bank.

- 9: Inscriptions on the rim of the jars indicate the volume, on average 40 amphorae, that is c. 1040 liters

Referencies:- 1: Tripolitania, David Mattingly 1995

- 2: Peter Jones, VENI VIDI VICI page 317

- 3: Gilbertson D.D., Hayes P.P., Barker G.W.W. and Hunt C.O. (1984). The UNESCO Libyan Valleys survey VII: An interim classification and functional analysis of ancient wall technology and land use. Libyan Studies, 15, 45-70.

- 4: P. Romanelli, Leptis Magna (Rome, 1925), 72.

- 5:S. Franchi, in La Tripolitania Settentrionale (Rome, 1913), I, 63.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.

We are committed to providing versions of our articles and interviews in several languages, but our first language is English.